Post #9 Work: Notes on Laboring Under an Illusion

Eleven children were using corrosive chemicals to clean as well as perilous “head splitters, jaw pullers, bandsaws, neck clippers and other equipment” at a Seaboard Triumph Foods pork processing plant in Sioux City, according to officials. This is the second time federal investigators have found children working at that particular Sioux City meat processing plant.

In Which I Gather Threads From the Past, in the Present

Freedom or Annihilation?

Before Auschwitz slave laborers were forced to craft the notorious entrance slogan Arbeit Macht Frei (Work Makes You Free), it had already been in use at Dachau in 1937, and as early as 1933 at a concentration camp holding communist prisoners. This three word phrase is now impossible to set free from that Nazi context, but two 21st century incidents seem like attempts to belie that.

In 2009, the sign was stolen and cut into three pieces by a gang of thieves hired by a founder of a far-right Swedish party. It was repaired in 2011, but a replica now stands in its place at Auschwitz. In 2019, Volkswagen CEO Herbert Diess joked that "ebit macht frie" (ebit means earnings before interest and taxes). Responding to criticism, Diess claimed in his "apology" that the reference was unintended. With a history like the Volkswagen company has, however, it seems like a classic Freudian slip, or at least a heartless joke made at the expense of millions.

In his Algemeiner opinion piece on the topic, Gabriel Eichler reminds readers that among the "more than 15,000 slave laborers from nearby concentration camps" working for Volkswagen there were "300 skilled metalworkers from the massive transports of Hungarian Jews in 1944" that had been handpicked from Auschwitz, and "650 Jewish women were transferred to assemble military munitions."

Of the scandal of Volkswagen's falsified diesel emissions (2009-2015), Eichler notes: The irony lost on many is that poisoning air with diesel gas goes back in history, when . . . Nazi Germany's skilled engineers developed and used mobile gas vans on large scale as an extermination method."

This gut-wrenching piece in The Nation looks closely at the horrible mistreatment of the women forced to work for Volkswagen; the appalling manner in which their babies were killed; and the gross inadequacy in the punishment of perpetrators.

As detailed in my post #5 on Nazi billionaires, forced labor was common, exploited across a range of German companies that are still in existence. Manufacturing subcamps were even built next to concentration camps, expressly to expedite matters for companies. This short video from Britannica gives us a glimpse of the practice of "annihilation through work," using archival footage and testimony from survivors:

Human Trafficking and Child Labor

I opened with those child workers endangered at the Iowa pork plant because I feel they exemplify the 21st century continuation of deeply disturbing attitudes about whose lives have value. Among recent government funding cuts are grants for programs that fight trafficking:

Furthermore, Project 2025 would give support to states such as Iowa, Indiana, and Florida, who wish to turn back the clock on child labor laws. Jonathan Berry served in the Department of Labor in the first Trump presidency, and in Project 2025 he proclaims the supposed benefits of hazardous work for teens.

With more than a little flavor of "work makes you free," Berry argues for underage labor as "independence." As Rebecca Gordon notes in her Truthout discussion:

"Young people, too, would acquire more “independence” thanks to Project 2025 — at least if what they want to do is work in more dangerous jobs where they are presently banned. As Berry explains:

“Some young adults show an interest in inherently dangerous jobs. Current rules forbid many young people, even if their family is running the business, from working in such jobs. This results in worker shortages in dangerous fields and often discourages otherwise interested young workers from trying the more dangerous job.”

The operative word here is “adults.” In fact, no laws presently exclude adults from hazardous work based on age. What Berry is talking about is allowing adolescents to perform such labor."

And of course it is no coincidence that child labor laws would be targeted at a time when migrant workers are under massive attack.

Civil Service Work and Fascism, Then

In his novel, 1984, George Orwell devotes substantial attention to the nature of his main character's work, and how he feels about it. Winston is employed in altering documents after the fact, to make them correspond to the desires of the Ministry. His work instructions "never stated or implied that an act of forgery was to be committed; always the reference was to slips, errors, misprints, or misquotations which it was necessary to put right in the interests of accuracy" (37). On deeper consideration, however, Winston realizes it's fabulation rather than forgery—

But actually, he thought as he readjusted the Ministry of Plenty's figures, it was not even forgery. It was merely the substitution of one piece of nonsense for another. Most of the material that you were dealing with had no connection with anything in the real world, not even the kind of connection that is contained in a direct lie. Statistics were just as much a fantasy in their original version as in their rectified version. A great deal of the time you were expected to make them up out of your head. (37)

Despite his recognition that he's fabricating nonsense, the task has a certain appeal:

Winston's greatest pleasure in life was in his work. Most of it was a tedious routine, but included in it there were also jobs so difficult and intricate that you could lose yourself in them as in the depths of a mathematical problem—delicate pieces of forgery in which you had nothing to guide you except your knowledge of the principles of Ingsoc and your estimate of what the Party wanted you to say. Winston was good at this kind of thing. (39)

In a violent, surveillance state offering few pleasures and no autonomy, these are moments where Winston's skill and creativity can be expressed. Even while in the service of something unworthy and soul-crushing.

Sebastian Haffner describes a similar absorption in precise mental work—undertaken in the midst of egregious state control—in his memoir, Defying Hitler. There's an allure in the intricacy of working with language and cases, that creates a temporary bastion against the disorder being wrought by the government.

Speaking as a writer focused on crafting pieces like this one for Finding Throughlines, I suspect that I understand the mechanisms at work here. The drive to create order amidst chaos is not itself a problem—except when it offers a false sense of a return to "normal."

Concerned about the Jewish boycott set to take effect the next day, Haffner finds in his labors a kind of welcome escape (until the SA enters to eject all Jewish judges and clerks). He describes the experience of working in the law library:

As always, the high-ceilinged, spacious room was filled with the inaudible electricity of many minds hard at work. In making pencil marks on paper, I was setting the instruments of the law to work on the details of my case, summarizing, comparing, weighing the importance of this or that word in a contract . . . When I scribbled a few words something happened, like the first cut in a surgical operation: a question was clarified, a component of a judicial decision put in place . . . . It was like a silent concert. I loved this atmosphere. (148)

In a manner that feels familiar to us now, this atmosphere is altered by the arrival of Hitler's "newcomers" among the court judges. Haffner watches with dismay as "the new member of the senate produced unheard-of-points of law in a fresh, confident voice," and would "quote Hitler," to "insist on some untenable decision." The older judges were, he notes,

used to failing candidates for the Assessor examination for spouting the kind of nonsense that was now being presented as the pinnacle of wisdom; but now this nonsense was backed by the full power of the state, by the threat of dismissal for lack of national reliability, loss of livelihood, the concentration camp . . . . They begged for a little understanding for the Civil Code and tried to save what could be saved. (190)

Haffner realized he "had no future here," feeling "as though I were at a deathbed" (191).

By this time, his father had retired from Civil Service. But visits from his former coworkers underscore what Sebastian witnessed in court:

Now and again, associates from his old department would visit my father . . . the conversations had become dreary and unchanging. My father would ask about a colleague, speaking his name. The visitor’s answer was a laconic “Clause Four” or “Clause Six.” Those were clauses from a recent law. It was called the Law for the Re-establishment of the Civil Service and its individual paragraphs allowed civil servants to be demoted, involuntarily retired, laid off with a lump sum, or sacked without any pension or payoff. Every clause contained a destiny. “Clause Four” was a devastating blow. “Clause Six” was demotion and humiliation. These numbers dominated conversations between civil servants.

One visit in particular illustrated how high the stakes had become.

One day the president of the department visited. He was much younger than my father and they had had their quarrels. . . . This time the visit was painful. The president, a man in his late forties, looked as old as my father did at seventy. His hair had gone completely white. My father told me afterward that he had often lost the thread of the conversation, not answered, and looked absentmindedly down at the floor. Then he had burst out, ‘It’s dreadful, my friend. Just dreadful.’ He had come to say goodbye. He was leaving Berlin to ‘crawl away somewhere in the country.’ He had just come from a concentration camp. He was “Clause Four.” (234-5)

And Now

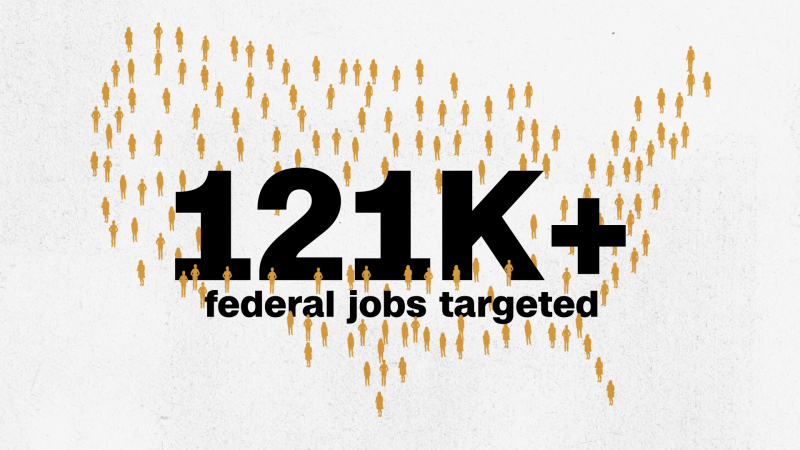

The current drastic slashing of governmental departments is causing incalculable societal, economic, and emotional damage:

In fact, the emotional damage has been quite intentional. Russell Vought—Trump's head of the government office of management and budget (OMB) and Project 2025 henchman—has openly stated that "we want the bureaucrats to be traumatically affected" and "we want to put them in trauma."

So far, those most subject to modern day camps/bodily detainment have been immigrant sheet metal workers, hair dressers, soccer players, and other unfortunate internationals simply going about their business or education while in the United States. But the throughline is clear. Those renditions and detentions have recently been followed by the arrest of two judges and a mayor, and threatened arrests of congressional representatives.

And while it all goes down, we face the disorienting experience so vividly described by Sebastian Haffner and George Orwell: that of trying to carry on with daily life and work while fundamental truths or norms are being violently upended.