What's in a Name: Murderous Metaphors

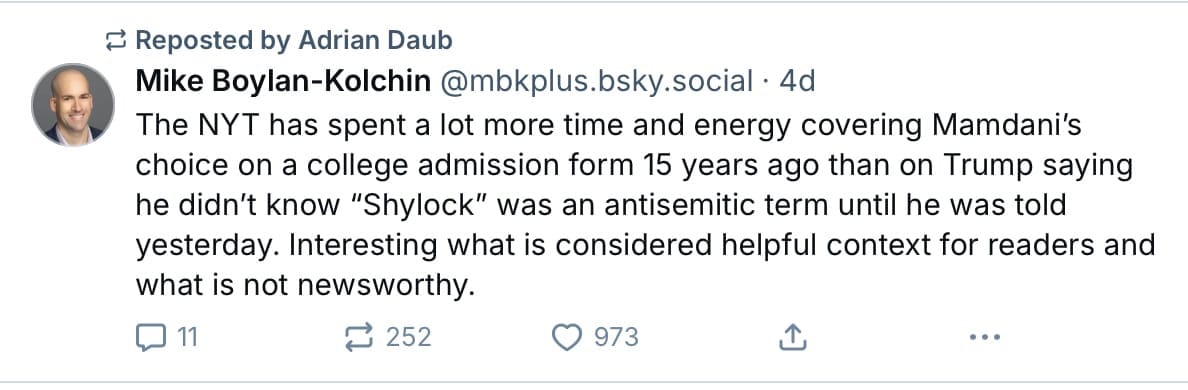

It's nearly impossible to keep up. Last week, right after I pushed the "publish" button on my article, "Poison Words: Language, Dehumanization, and Death," I heard about the president's anti-semitic reference to "bad bankers" as "Shylocks." And, of course, there's the ongoing effort to racially-smear NYC mayoral candidate, Zohran Mamdani.

At first, I thought there might be an upside to the dog whistles becoming more audible to everyone: it might be easier to mobilize resistance now that the problem is so obvious. That was probably naive of me. Now, I'm more concerned that all this whistling is actually normalizing a set of atrocious ideas in service to a police state.

Last week, I wrote about how easily schoolyard insults kick in, like a reflex—moron, idiot, cretin, imbecile, the r-word—and how these, as well as Trump's use of the "low IQ" insult have roots in the history of eugenics here and abroad. As the first "semester" of my Learn, Imagine, Act project draws to a close, my main takeaway is: we need to be informed and discerning about context. When someone with unchecked power repeats the toxic tropes discussed in "Poison Words," firing up the internet echo chamber while he expands carceral systems, we're not on the schoolyard. We're watching a propaganda campaign.

It's meant to control through division. Labeling and "othering" are key tools. Andrea Pitzer, the author of One Long Night: A Global History of Concentration Camps notes in her Youtube talk below, that "every country has fault lines that unscrupulous political actors can use to divide a country's population." I used this metaphor myself back in January, when I remarked to my husband that "these people are applying dynamite to all of the country's existing fault lines." He'd replied, simply, "that's what fascists do."

Pitzer's new half-hour presentation provides a clear definition and historic timeline of concentration camps. She also offers a much-needed discussion of why it matters what we call the Florida camp, which is literally being sold to us as "Alligator Alcatraz."

My sense is that we are being "softened up" to accept this as rapidly as possible, which is concerning, given this observation from Pitzer:

"It usually takes years of propaganda, regardless, to get people to accept camps, but exposed to enough, a majority will either embrace their neighbors being rounded up, or tolerate it out of fear and confusion."

Pitzer notes in her book that "camps require the removal of a population from a society with all its accompanying rights, relationships, and connections to humanity." This certainly applies to the hundreds of men sent to El Salvador without criminal records or due process. Pitzer cites Hannah Arendt's description of what happens after that removal:

"the human masses sealed off in them are treated as if they no longer existed, as if what happened to them were no longer of interest to anybody, as if they were already dead and some evil spirit gone mad were amusing himself by stopping them for a while between life and death" (7).

I highly recommend watching Pitzer's video, not only for the clarity she provides, but for the suggestions for action that she ends with.

Timothy Snyder's July 4th piece is also unequivocal and admonitory:

"What happens next in the U.S.? Workers who are presented as "undocumented" will be taken to the camps. Perhaps they will work in the camps themselves, as slaves to government projects. But more likely they will be offered to American companies on special terms: a one-time payment to the government, for example, with no need for wages or benefits. In the simplest version, and perhaps the most likely, detained people will be offered back to the companies for which they were just working. Their stay in the concentration camp will be presented as a purge or a legalization for which companies should be grateful. Trump has already said that this is the idea, calling it 'owner responsibility.'"

We need to do everything in our power to prevent this eventuality.

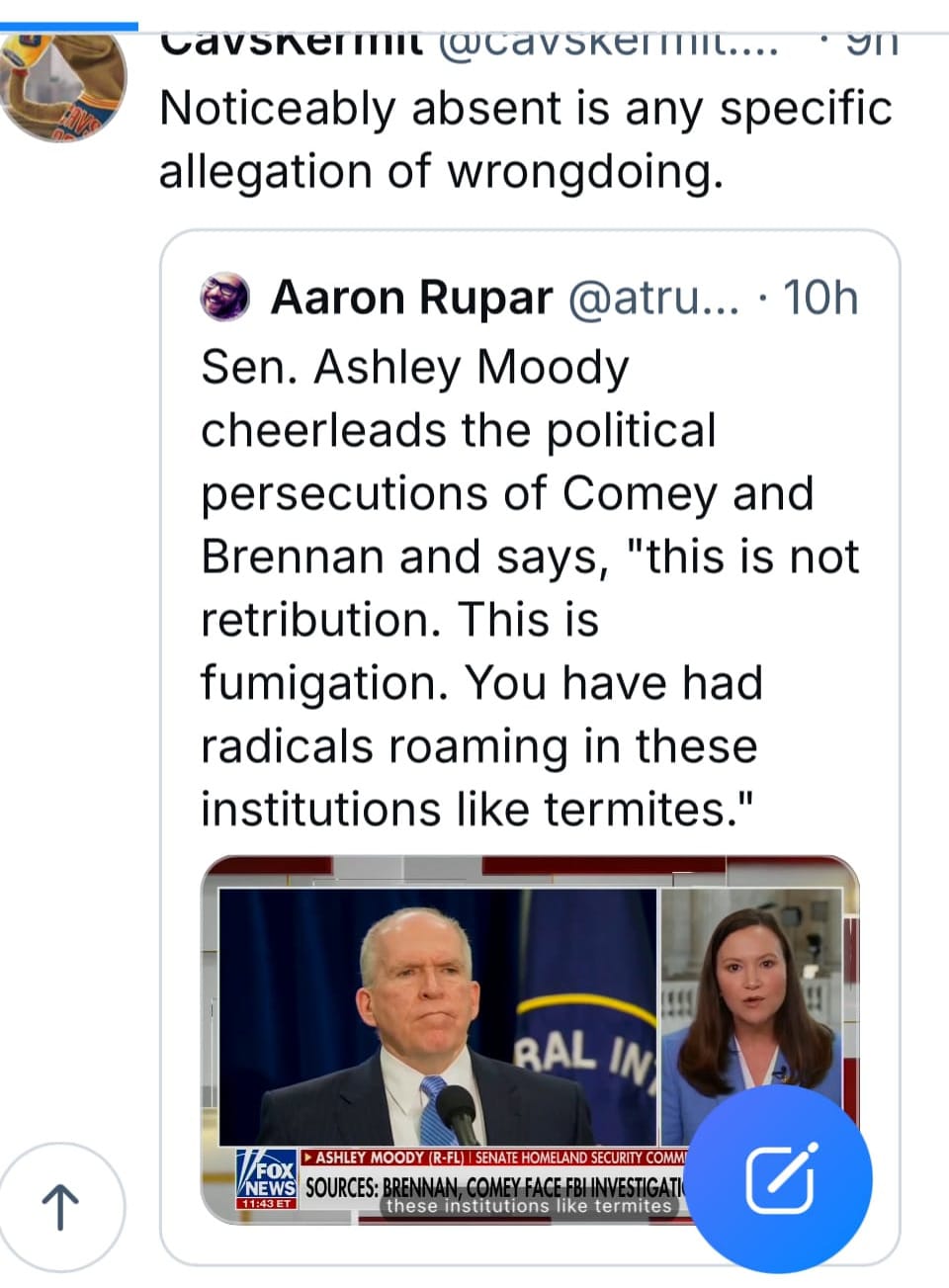

Last week I also promised to talk about the politically dehumanizing use of the language of parasitism and—as we've seen this very week—infestation more generally:

I know what to watch out for, but this one is a stunning example of the genre. Hopefully, lots of us can recognize it without needing much more contextualization. I'll add some anyway.

It's really just a follow-on from this re-post of a DOGE meme by Musk a few months ago:

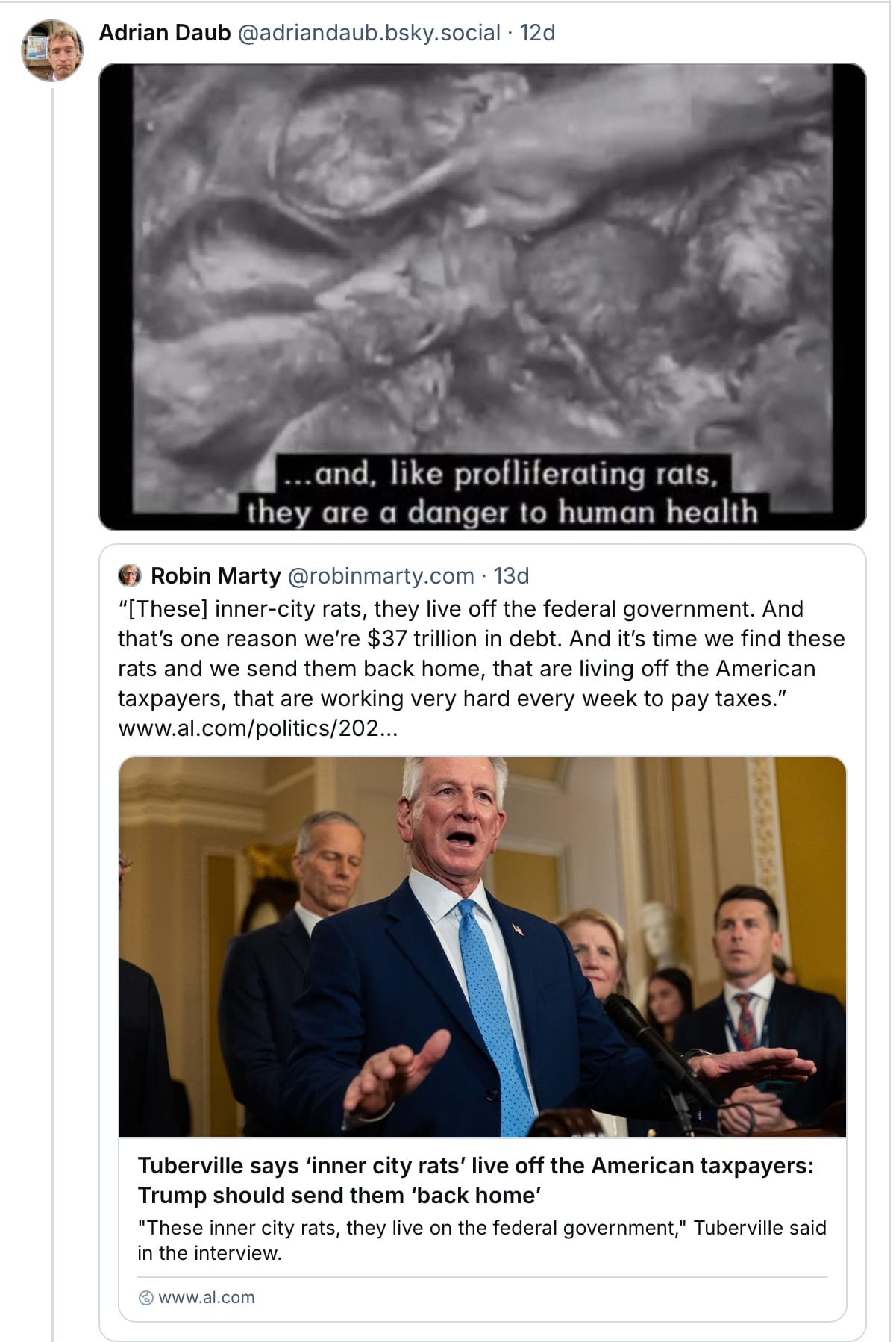

And these recent slurs from Tuberville:

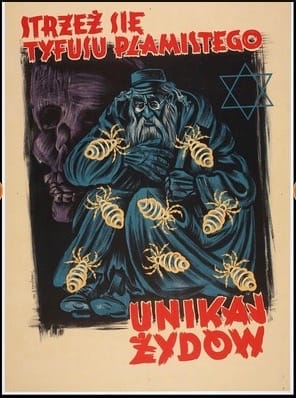

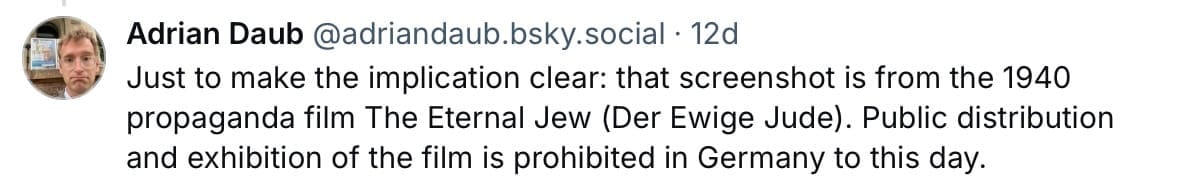

As Adrian Daub points out on Blue Sky, these pest tropes are in a direct line of descent from Nazi propaganda. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum is an excellent resource for understanding the Reich's propaganda machine:

Not only were Jews vilified as vectors for disease-carrying insects, they were also depicted as the insects themselves. In his book, Insectopedia, Hugh Raffles points out that Jews had long been compared in Germany to mongrels and pigs, but, he comments,

“More destructive—and more insinuating —was the association of the Jew with the shadowy figure of the parasite, a figure that infests the individual body, the population, and of course, the body politic, that does so in both obvious and unexpected ways, and that invites innovative interventions and controls.”

This rhetoric carried forward into literal extermination efforts. In 1943, Heinrich Himmler said,

“Antisemitism is exactly the same as delousing. Getting rid of lice is not a question of ideology. It is a matter of cleanliness. In just the same way, antisemitism, for us, has not been a question of ideology, but a matter of cleanliness, which now will soon have been dealt with. We shall soon be deloused. We have only 20,000 lice left, and then the matter is finished within the whole of Germany” (141).

Raffles notes that “this is the period in which we see the development of those technologies of disease control that achieve a kind of fulfillment at Auschwitz: collective showers, bacteriological soaps, chemical gas, cremation . . . These technologies were already compulsory features at a network of border control stations . . .” that worked to discourage migrants (158).

I understand the urge to retort, "no, you are the parasite," when a billionaire—who has extracted some portion of his wealth from society through questionable, perhaps even illegal, means—refers to ordinary working people as parasites. I won't fault you for it if you do. The genocidal history of the term's use, however, compels me to avoid it. I'll reserve it for organisms who operate according to their genetic coding, rather than their avarice or fascism.

We should learn from the 20th century: when made by powerful people and their followers, these references to humans as pests should not be dismissed as mere toothless posturing. The more we can understand this history, the better able we are to stand up against today's deployment of the language, and the policies and concentration camps it helps build.

Sharing these resources with others can be a good first step in helping create our repertoire of constructive responses. Again, thank you for reading this far, and for subscribing, commenting, and sharing!

https://exhibitions.ushmm.org/propaganda/1918-1933/weimar-democracy-in-crisis