Tending and Seeding: Making Sure There Will Be New Growth

As I write this, my tiny habitat garden already shows autumn's encroachment. Only the asters, goldenrods, and brown-eyed susans are still in bloom, while the echinacea and yarrow flowers look like burnt toast. Over the last few years, I've been learning to garden more for birds and insects, especially prioritizing plants that are indigenous to the region. It has truly been a case of "if you build it they will come." What a joy it's been, to witness the arrival of such a variety of pollinators in my concentrated urban neighborhood, in an abundance I never could have imagined.

It sounds funny to say that I am inspired by insects, but it is true. Seeing their activity in the face of all the threats to their existence motivates me, and offers hope for us all.

So, as I embark on the second semester of the first year of what we might call my "47th presidential term college education," I'm choosing to write about gardening as an act of resistance and renewal. I took a little longer break than I had planned from my Learn, Imagine, Act project, because of all the—waves hands at everything—chaos and cruelty. It keeps ratcheting up to new levels, with no clear end in sight. We need to stay informed and active. But we must also pace ourselves, or we will become like Beatrix Potter's character in The Tailor of Gloucester, "undone and worn to a raveling."

I feel an urgent imperative to learn, write, and speak out about the history (and present) of concentration camps, political violence, and freedom of speech. But at this particular moment, I'm also drawn to sharing counteracting visions. I'm looking for prescriptions for prophylactics and antidotes that come from the land, powerful natural forms of helping and healing. And I'm planting for new growth in the future: boneset, cardinal flower, spotted bee balm.

The Greek language gifted us these two common medical terms. Prophylactic comes from "pro"= before, and "phulassein"= to guard. Antidote comes from "anti"= against, and "didonai"= to give. For these times, we need measures that can be "before guards" against oncoming assaults, as well as remedies given against toxicity we've already been exposed to. People used to turn, quite literally, to their gardens for such substances. I suspect we can find both literal and metaphorical remedies there now. As Joni Mitchell told us so long ago in the song, Woodstock: "we've got to get ourselves back to the garden."

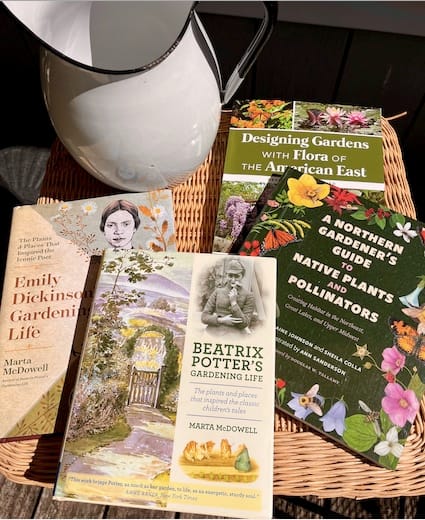

That's why I've recently added the books pictured above to my Learn, Imagine, Act curriculum (and as always, I'm interested in your recommendations for my reading, listening, watching list). The two books pictured on the right are for information, the two on the left are for inspiration.

So far, the Learn, Imagine, Act curriculum has been very helpful for anchoring my attention and preventing excessive, random doomscrolling. But one's focus cannot be solely on filling information gaps about our worst political problems. It is also important to generate the energy and imagination we need for creating a more sustainable and just world. This week's book selections can help us do that.

I had the pleasure of visiting both writers' houses this summer, walking through their gardens and savoring the moments inside their exceptionally well-preserved writing and domestic spaces. For all their talents, Emily Dickinson (1830-1886), and Beatrix Potter (1866-1943) labored under the societal restrictions on females of their times. Their status as white women from affluent families facilitated their creative efforts and kept them from disappearing from the historical record the way so many other women have. While holding that awareness, I found it gratifying to see these repositories full of concrete evidence of their lives and works.

Dickinson lived through the Civil War, and Potter the first and second World Wars in these spaces. An encounter with their virtually unchanged homes and gardens felt like it was expanding my perspective on the turbulence of our time. Author and gardener Marta McDowell's books offer a gorgeous view—interspersed with samples of their work—of these writers' relationships with their gardens. It was about a nourishment that went far beyond food.

Both writers took an active interest in the life of their landscapes. "Botanizing" was a permissible pastime for proper young women. Dickinson pursued it with passion and an independence verging on impropriety. She called her favorite plants "her darlings of the soil," and referred to mushrooms as "the Elf of Plants."

Potter herself went all in for the study of mycology. She collected, grew, and painted fungi, and had the audacity to write up her studies in a paper she submitted to a male-only Linnean Society meeting. Potter was unable to advance her findings in that forum, and Dickinson herself never sought publication. But in subtle ways, these writers have influenced the vision and vocabulary of readers all over the world, through their poems and stories depicting experiences in nature .

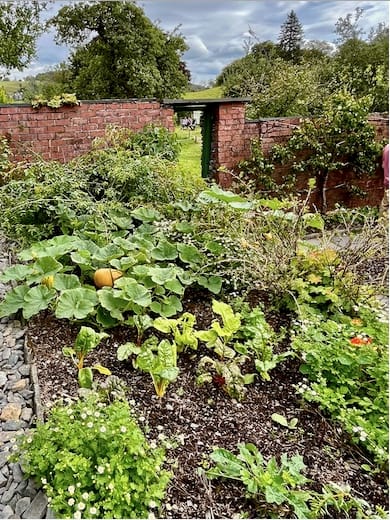

The Dickinson house, Emily's famous house dress and bedroom where she composed her poetry, and the white oak her brother planted

A less known fact about Potter is that in later life, she moved out of London to the Lake District, and became an avid farmer. She took a deep interest in preserving the local Herdwick sheep breed. With the help of William Heelis, whom she married in her middle age, she carefully acquired farmland when it came up for sale, in order to protect it from development as the area became more popular as a tourist attraction. The couple had no children, and at their deaths, they gifted over 4,000 acres of conserved land to the National Trust.

Beatrix Potter's Hill Top Farm in England's Lake District, complete with the model for Mr. McGregor's garden

The two guidebooks are recent, published in 2023 and 2024, and offer invaluable tools for amateur and professional gardeners alike. Because of the geographically-bounded nature of many plant species, both books focus on advice for particular regions. Lorraine Johnson and Sheila Colla's book, A Northern Gardener's Guide to Native Plants and Pollinators is for "Creating habitat in the Northeast, Great Lakes, and Upper Midwest". Carolyn Summers and Kate Brittenham's book is entitled Designing Gardens with Flora of the American East. The books are lushly illustrated with photos or botanical paintings; include a range of specific garden plans; and offer extensive resources and appendices.

The first book will familiarize you with individual plant species; their characteristics; the insects they support; and their contribution to the garden. The second provides similar facts, as well as detailing the science on ecosystem damages done by nonindigenous plants because their growth is unchecked. There are some surprises, such as the finding in Connecticut that "Japanese barberry has been found to harbor abnormally high levels of lyme-infected ticks" (98) and the propensity of English Ivy for "killing trees from the bottom up, leaving them looking somewhat like giant stalks of broccoli" (113).

The authors of Designing Gardens offer especially helpful advice about "appropriate alternatives"—plants to replace problematic but popular landscaping choices such as forsythia, butterfly bush, and burning bush. Whether you are setting out to plan and plant a native garden, or simply dreaming of gardens during a dark, north-eastern winter, these references have much to offer.

And, in keeping with the theme of antidotes and prophylactics, these guidebooks offer both literal and metaphorical wisdom with wider applications. Here are a few observations to ponder:

-About co-evolved relationships of healing: "bumblebees infected with a common intestinal parasite self-medicate with plant chemicals found naturally in nectar and pollen. When . . . infected . . . they seek out white turtlehead flowers containing the highest concentrations of these chemicals" (Northerner's Guide, 15).

-About a thicket-forming invasive shrub that is a vicious spreader: "Removal takes great effort; far better is to prevent its establishment (Designing Gardens, 104).

-On questioning labels: "do not assume that every plant that shows up unannounced bearing scruffy leaves is, in fact, a weed" ( DG, 77).

-About industrial horticulture: "Perhaps we need to ask whether it is possible for the dominant industry model to redesign itself into a truly 'green' force for positive change. It may be time for a more locally based cooperative model" (DG, 143).

-About people's power to change things, starting at home: "it may not seem like your green space can be a place to enact change, but every green space is now the front line against climate change and habitat degradation" (DG, 193). Case in point: "subdivisions or housing developments are usually some of the most ecologically dead landscapes . . . . What if, instead, each resident planted a small woodland edge in their backyard, along shared property lines?" (DG, 183)

Douglas Tallamy's foreword to A Northern Gardener's Guide adds some statistics to the "people power" concept: "Private landowners hold enormous conservation potential because there are so many of them. In the United States, 135 million acres are now in residential landscapes. The good news is that hundreds of millions of people live in, and thus manage, those landscapes. With a little education, all of us can come to realize that sustainable earth stewardship is not something we can ignore or practice only if we feel like it. It is essential" (viii).

Tallamy is the co-founder of the Home Grown National Park project, which is a great place to learn more about how to exercise people power through plant choices. There's even an end-of-summer sale on starter kits, including one for folks who may only have room for a container garden. Fall is a great time to plant native species, and time is of the essence when acting for positive change.