Seeing Beyond the AI Mirror

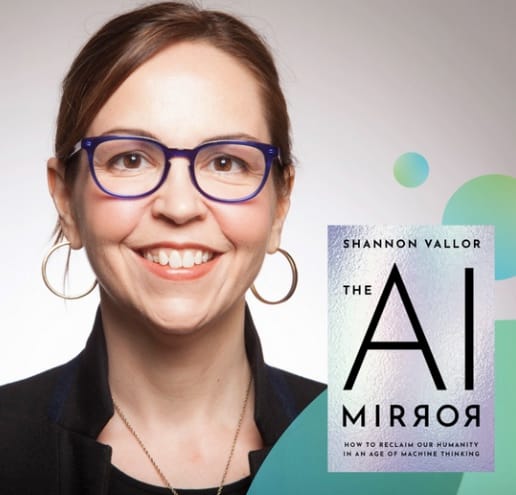

In my last post about avoiding technologic overreach, I introduced ethics and philosophy professor Shannon Vallor's 2024 book, The AI Mirror: How to Reclaim Our Humanity in an Age of Machine Thinking. I also added to some lines of questioning I'd broached in my November 7 post, Raising Questions. This week I'd like to look at Vallor's arguments in more depth.

My discussion here will only be able to skim the surface of this deeply thoughtful book. With her academic background and her experience as a former AI ethicist at Google, Vallor offers a unique lens on the issues raised by these technologies. In what she acknowledges is a polemic, Vallor makes an urgent call to reckoning: we must question what the AI mirror is reflecting about us, if we are to find our way to a more sustainable and balanced relationship with the planet, ourselves, and other life forms.

She uses the metaphor of a mirror for AI, to clarify both its reflective and potentially distorting qualities, arguing that the database fueling its images constitutes only a biased slice of our past. As such, it will not only magnify inequities and errors, but also foreclose on as-yet unimagined possibilities. She believes that although we are running short of time, we still have a chance to exert control, by cultivating moral wisdom, respect for ourselves as human beings, and political will. As tough as that all sounds right about now—indeed, she calls it a "heroic project"—she does give examples from times in history where we have at least partly succeeded.

After finishing her book, I went back to the 80 questions to ask of technology (see link below). Many of these now look to me more like queries to make about physical tools—ones we might still have some conscious choice to use or refuse—instead of these digital modes that are slipping, often unasked for, into so many of our daily routines. In light of Vallor's work, I think question 26, whom does it benefit?; question 57, does it concentrate or equalize power?; and question 58, who is writing/controlling its narrative? are particularly relevant.

But we also need to add these: who owns it? and who sets the boundaries for its application and oversees its adherence to them?

As so many of the actions of the current administration have illustrated this year, technological power brokers have achieved a high degree of control over the body politic. Here's how Vallor describes our situation:

"a handful of multinational technology companies now compete with governments as world powers, while simultaneously owning the platforms that structure and shape the very media cultures and public conversations that, in democratic societies, are supposed to legitimate power and hold it accountable" (175).

How well can we expect this set up to work for the citizenry? And, as has become even clearer this year, it isn't just faceless companies operating according to impersonal corporate models. It's also individual billionaires. Meanwhile, working people's financial lives have grown more precarious, their resources dwindling along with their capacity to pay close attention.

It brings to mind the John Lennon quote, "life is what happens when you're busy making other plans." The cumulative growth of these power structures has gone unnoticed for many of us, through rapidly reinforcing feedback loops, until we're shaken to attention, asking, "wait, when did these people/companies get this big?"

For more about how platforms influence our experiences of freedom and democracy, see my discussion of Renée DiResta's book Invisible Rulers:

This rapid growth and consolidation of power has set off a slew of new ripple effects. Considering the development of engineering standards and professional ethics in the 20th century, Vallor argues that our current technological acceleration has far surpassed the capacity of these codes. As she describes it,

"Today's engineers and technologists—especially those who design, develop, deploy, or maintain advanced AI systems—are now being asked to exercise sound judgment about their work's impact on a far more expansive set of moral goods, from social fairness and justice, to privacy and autonomy, to the transparency and accountability of sociotechnical systems, to democratic health and the sustainability of the planet." (170)

That's a huge assignment for any profession. I think Vallor is right to ask, "Are today's AI engineers and developers educated and professionalized to bear that kind of responsibility?"

Given that regulatory systems have also failed to keep pace, and "modern institutions have long severed scientific knowledge and technical skill from political wisdom and moral responsibility," the answer would seem to be a resounding no. This is not a problem that can be fixed with a few tweaks to the curriculum, however. There's a much larger story to be attended to:

"Even for AI tools with considerable polypotency—the potential to be used in many different ways, by different people, to accomplish many different things—the uses and effects that actually come to pass are typically steered by the dominant values of the social context in which the tool emerges." (140)

It is important to reiterate here that Vallor is not opposed to AI. Yes, her book takes us through a careful analysis of the flaws, risks, and outright dangers of many forms/uses of AI as it infiltrates so many of our social structures. But as a philosopher who is asserting the need to develop "technomoral wisdom" to guide our uses, Vallor consistently swings our focus back to human, rather than artificial, intelligence:

"I'll say it again: AI is not the problem here. The problem is our unwillingness to step back from our tools to reevaluate the patterns they are reproducing—even the supposedly virtuous ones" (183).

In a society that incentivizes productivity and values efficiency and profit, what we prize may further entrap and even dehumanize us.

"Our economic order has long rewarded creators who work like machines" she points out, arguing that "AI can devalue our humanity only because we already devalued it to ourselves" (142). No wonder the "number of apps for auto-chatbot therapy and mindfulness practice dwarfs the handful of apps designed to facilitate labor organizing" (188).

Dismissing sci-fi dystopia scenarios where AI insurrections drive human demise, Vallor believes that "AI-driven calamities can only happen from people abandoning the moral responsibility not to unleash their tools into a world unsurpervised and unregulated." It is going to require "the moral and political will to govern AI systems, or more accurately, the will to govern the humans and corporations who build and deploy AI," not merely to "mitigate their current harms" but to "redirect their power to new and better ends. We need a new collective agreement on what technologies are for" (196).

To arrive at that, we also need to recognize and repudiate the existence of what Vallor calls "a rising techno-theocracy" that believes it is creating "a divine pilot, a new superhuman Creation built to finally relieve us of the burdens of our heavy and clumsily wielded moral, political, and intellectual freedom" (218). (As far as I can tell, the so-called effective altruists, and Peter Thiel, with his recent pronouncements about the "anti-christ," just may be bizarre fellow-travellers in these lines of thought.)

In a fascinating passage, Vallor cites Cave and Dihal's book, Imagining AI. They posit

"the roots of this theology in a 'California ideology' that mirrors the earlier American settler myth, which saw the push to the west and colonization of Indigenous lands as the fateful 'second creation' of humankind. Like that ideology, which sought to overwrite the values and institutions of Indigenous Americans and justify it with a religious claim of manifest destiny, today's AI theology seeks to overwrite our human agency and potential with an imagined 'superhuman' intelligence that renders ours into insignificance." (218)

If we hope to escape using AI to repeat the destructive colonizing patterns of our past and present, we need to resist the tendency to valorize efficiency, disruption and transformation for their own sake.

If we wish to find healthy solutions to our planetary crisis, Vallor believes, we will probably need the help of AI tools. Our best chances lie in prioritizing care, community, and creativity, and being guided by these humane values in our uses of AI.