Post #7: Tools for Our Timeline

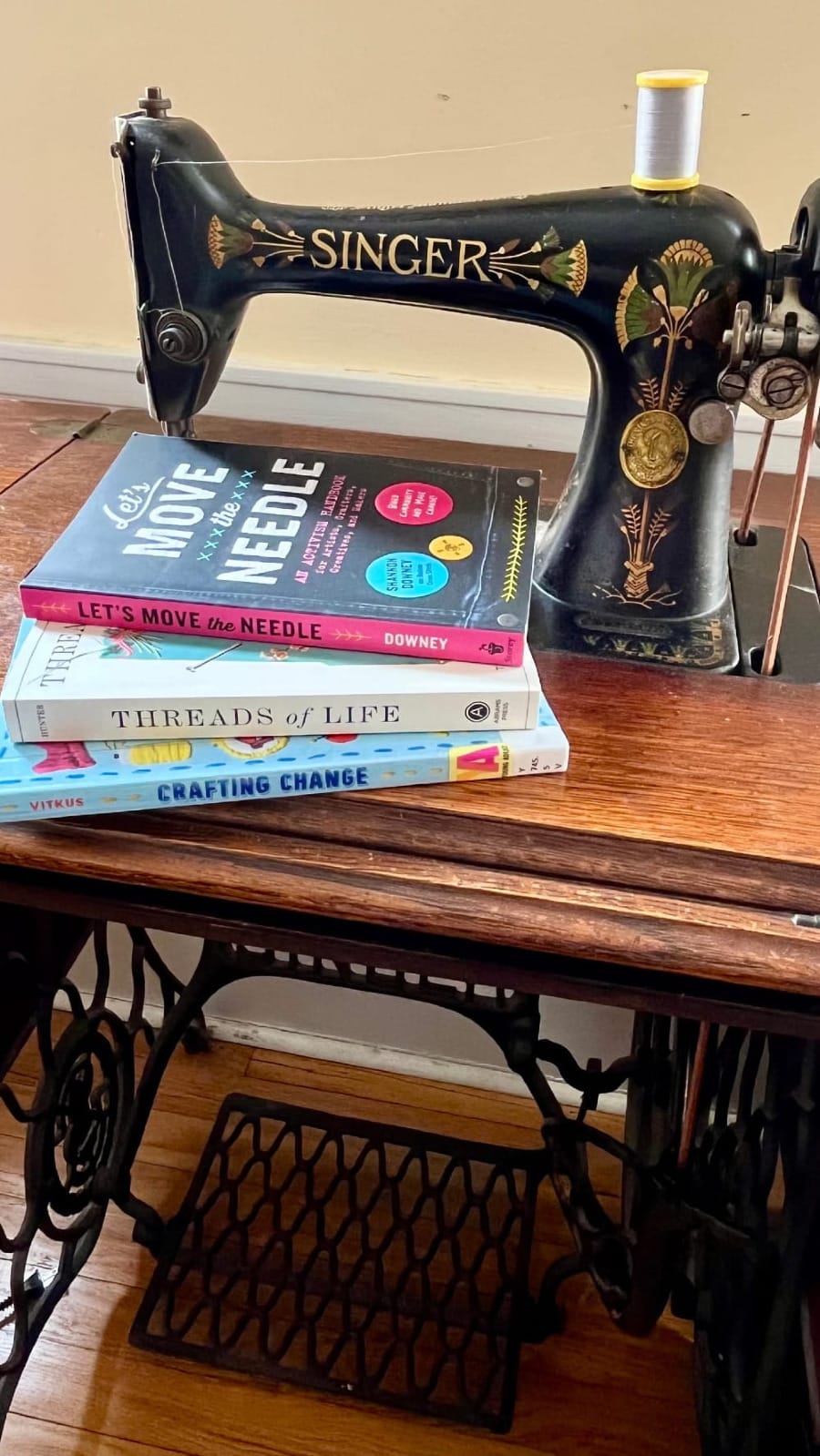

“Craft is the greatest tool I’ve ever stumbled upon for building communities and mobilizing them to take actions that will bring about actual social change. In fact, I call myself a community organizer disguised as a fiber artist. I trick people into hanging out together by promising embroidery workshops, and what we actually do is have community gatherings where we identify and find ways to work toward common goals,” Shannon Downey, Let's Move the Needle (9).

This week I’m inviting you to spend more time with craft and beauty–with the healing, memory work, connection-building, and creativity that can arise from sharing the work of our hands together. Before we slip back into discussing the titles from Learn, Imagine, Act, I'd like to begin with a personal example,

Last night I shot past my personal limit for screen time, staying online way beyond my 9 pm detachment goal. While scanning headlines, I'd swallowed an indigestible helping of news about cruelty, ignorance, and destruction, with a side of outright ghoulishness. I felt too wired to sleep. So, late as it was, I turned to poetry as an antidote.

Unlike fiction and non-fiction, which I often draft at the keyboard, poetry builds itself out differently for me. A poem’s bones, sinews, and organs find form in the slow friction between pen and paper. Last night, I was ostensibly writing about childhood experiences: peering under creek rocks, hunting for crawdads and mudpuppies, absorbed in nature.

But there was more hiding under those rocks. Family lore and secrets, mysteries of biology and genetics, and a dark realization that, for all their precautionary tales, adults often fail to keep children safe. Sounds as if I simply traded one set of nightmare materials for another, right? But the difference lies in the active role afforded by the crafting of word and image.

No longer the passive receiver of catastrophes occurring mostly outside my sphere of influence, I was shaping a memory, crystalizing it into comprehension. I was creating a narrative event that can stand outside myself and be shared with others. Of the range of categories Shannon Downey lists for craftivism in Let’s Move the Needle, my poem would fit under healing; record keeping; and reflection and understanding (19-21). And a key part of all of these is naming.

Because language and image are being deployed so egregiously to lie to us and create false realities, I’m particularly interested in naming as an act of resistance. By naming events and those harmed by them, and by naming our values, we can energize our actions and better forge the tools to protect and repair.

In Post #4 of this series, I quoted Masha Gessen’s statement about the need to “find names for things that have not, in the past, been observed or been seen as deserving of description" (Surviving Autocracy, 96). Let's stop here a moment, to consider how much of Project 2025 is an attempt to blot out names, people, and ways of being in the world that its authors deem undeserving of description.

These include immigrants, indigenous people, people of color, LGBTQIA+ people, the disabled, women, dissidents of any kind. In Post #2, on unburial, I talked about artist Gunter Demnig's stolpersteine or stumbling stones project, with over 100,000 plaques now scattered across the streets of Europe. These name the Jewish residents formerly living there, whom the Nazis deported and/or killed.

Stumbling stones have a place-based resonance and a distinctive power in being semi-permanent installations. But they also share the motivation of memorials crafted by others in more fragile media. I'd like to share a few of these, mentioned in Downey’s book, described in Clare Hunter’s Threads of Life, and profiled in Crafting Change: Handmade Activism, Past and Present, a book for young readers by Jessica Vitkus.

In a chapter titled Captivity, Hunter describes how women held in a WW2 Japanese prisoner of war camp in Singapore embroidered their own and each other’s signatures on small pieces of cloth, collecting autographs from hundreds of other prisoners to preserve their memories and identities. One, Hilda Lacey, combined the 216 she had collected, and “stitched a dangerous and defiant border to document the conditions of camp life: a rice bucket to show the scarcity of food; kiri (the deep bowing required of prisoners to their guards) . . . a prison cell sewn to arithmetic scale; an emaciated man in a loin cloth digging for nutrition that he would have no right to claim” (57). These are subversive assertions of one's right to exist, able to outlive their makers.

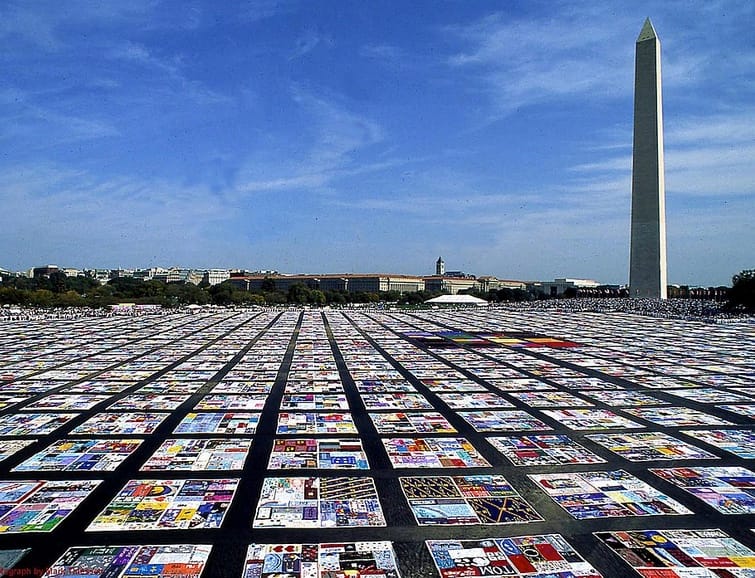

As needlework scholar Mariah Gruner points out in Crafting Change, “contemporary craftivists are taking part in a very long tradition of reframing the meanings of ‘domestic’ craft” (99). The AIDs Memorial Quilt became probably the best known such project. When it was first displayed in 1987, it consisted of 1,920 panels. As of Downey’s writing, there were 50,000 panels and it weighed in at 54 tons.

It's important to note that the quilt is an ongoing project. Quilter Julie Rhoad of the NAMES Project Foundation/AIDS Memorial Quilt told Vitkus that people send in quilt panels at a rate of “about three hundred a year. In a peak year, up to eight hundred” (114).

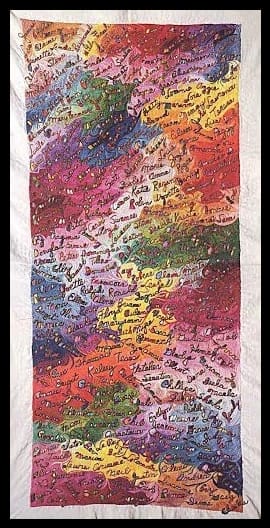

In her chapter called Protest, covering banners from the suffragettes to the Greenham Common women's peace camp, Hunter also tells the story of a 1985 U.S. anti-war project, The Ribbon. This account surprised me, as I had never heard about this large scale sewing project, marking the 40th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Mother and teacher Justine Merritt’s dream was that people would sew peace panels in a “ribbon,” long enough to wrap around the Pentagon. As Hunter notes, “The Ribbon was the idea of a single woman who lacked any of the resources to see her plan through” (138). Merritt's personal panel resembles the POW signature embroidery as well as those stitched on handkerchiefs by incarcerated suffragettes: it is covered with the embroidered names of loved ones.

Photo: Wikimedia, Michelemariesimone, Cc.3.0

In 1982, Merritt managed to send out a newsletter to 600 people. But even in this mostly pre-digital era, “by 1985, there was a mailing list of 10,000 names and 25,000 panels had been made.” Interestingly, according to a survey, “95 percent of those who responded were women who would not describe themselves as political activists” (139). By that August, 20,000 participants showed up in D.C., where,

“The Ribbon didn’t just wrap around the Pentagon. It spread across the Arlington Memorial Bridge, around the Lincoln Memorial, around the capitol, back up the Mall, back to the Lincoln Memorial and the Pentagon. It was fifteen miles long” (140).

The Ribbon's strapline: “Honor the diversity, celebrate the unity.”

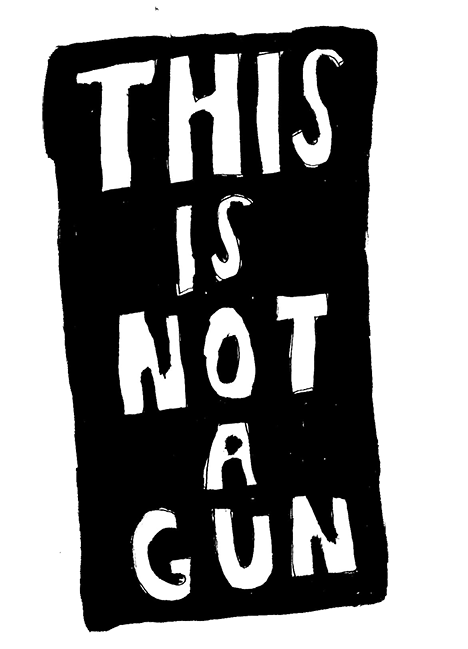

Other inspiring contemporary projects that work by naming or memorializing are Melissa Blount’s Black Girl Magic portraits, Breonna Postcards, and Transgender Lives Matter Witness Quilt; Cara Levine’s This is Not a Gun Project; and the Social Justice Sewing Academy, all featured in Crafting Change.

Shannon Downey also highlights Gone But Not Forgotten, “a community quilting project that documents the individuals killed by the Chicago Police Department or while in police custody from 2006-2016. According to artist Rachel Wallis, this forty foot long quilt memorializes 144 people, some of whose “names and stories remain unknown” (39).

https://www.rachelawallis.com/gone-but-not-forgotten.html