Post #6: Throughlines in Thread Lines

"Shape by your skirt a together-connectedness, /Unite multiple forms, colours and lines; / In the stream of historic events / Embroider the design with your heart and your hand"*

If you've been following along with me these last few weeks, you'll know that I've been sharing some heavy materials from our Learn, Imagine, Act resource list (see Post #2). The country is still very much in a state of emergency. But there's a limit to how long one's nervous system can sustain focus on multiple crises.

Yes, our readings on tyranny, autocracy, and Nazis are elucidating. I'm finding they can offer clarity and help steel one's resolve. However, I'm currently in a moment where I need to think about art and craft: acts of creativity rather than destruction, acts of resistance, and acts that celebrate the beauty and diversity of existence.

I'm seeing a lot of people asking what they can do. What actions can they take to stand up against injustices? How can we work toward a society that cares for everyone– including the environment and the more-than-human community? The two writers I feature today provide different kinds of answers and inspiration, as we consider how we might find our agency individually and together.

The first is Clare Hunter, whose book, Threads of Life: A History of the World Through the Eye of a Needle has definitely found a place in the Learn, Imagine, Act curriculum. Hunter offers an expansive perspective–historically and globally–on the role of needle and thread in human lives. She traces the power of stitching in unexpected places, including prisoner of war camps, psychiatric wards, prisons, and protests. Her scope also takes in traditional needle workers' responses to colonization and ethnicity-based oppression, as well as to forces of modernization and even tourism. As a community textile artist herself, Hunter portrays her subjects with a profound combination of scholarship and sensitivity. The book is beautifully written.

Organized around chapter headings such as Power, Frailty, Captivity, Identity, Connection, etc., Threads of Life provides a wealth of compelling examples. Through their skills at embroidery and other forms of sewing, men and women, but primarily women, have asserted their agency and identity, their cultural heritage, their family connections, their political views, and even coded messages.

Let's look briefly at the story of Dutch resistance fighter, Mies Boissevain-van Lennep. Her family members suffered both imprisonment and execution for aiding Jews. She survived Ravensbruck camp. There, she had drawn strength from a piece of patchwork: "the scarf had been fashioned by friends from tiny, bright fabric remnants from her own life: her children's clothes, her dance gowns, scraps from friends' and fellow resistance fighters' clothes" (80).

It would be easy to underestimate the impact of such a small item. But as Hunter explains, "it had been smuggled in as a touchstone of support, to remind her of who she was. That scarf had become her talisman of survival." After the war, she encouraged Dutch women to create a "skirt of life," or "magic skirt of reconstruction," to "publicly demonstrate the courage, resolve and solidarity of Dutch women, to remind others of women's place in Holland's history and their right to play a part in forging its future."

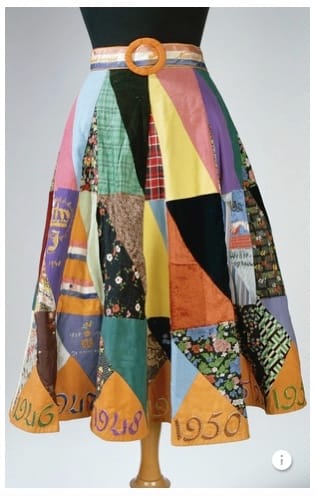

In an organized effort that included registering and giving each skirt an official stamp, participants created at least 4,000 of these patchwork skirts. They were made of "cloth fragments that held memory: the remnants of a hidden child's coat, a dead son's shirt, fabric from a refugee's coat, parachute silk . . ." (80). These skirts were meant to be "therapeutic as well as symbolic."

Hunter describes one, made by Mrs. J. de Jong-Brouwer:

The skirt has sixty patches on which are embossed vignettes of a war-torn Holland: a candle to record electricity shortages; a fingerprint to represent the enforced carrying of identity cards during German occupation; a chocolate bar, one of the small luxuries that appeared after liberation. The Jewish yellow star sits alongside the Nazis' own emblem, the swastika. Kidnappings, arrests, executions are all documented.

For more about this history and additional examples of the skirts, see this article: https://www.europeana.eu/hu/stories/liberation-skirts-how-post-war-upcycling-became-a-symbol-of-female-solidarity

The lines* quoted at the beginning of this essay are the first stanza of the "Hymn of the National Celebration Skirt." The second stanza aspires to a resilience across time:

Stamp your skirt with the mark of your days,/ Colour your flag with what Was and Will Be;/ The Present, the Past--merrily borne,/ Let them adorn your costume, your family, your life.

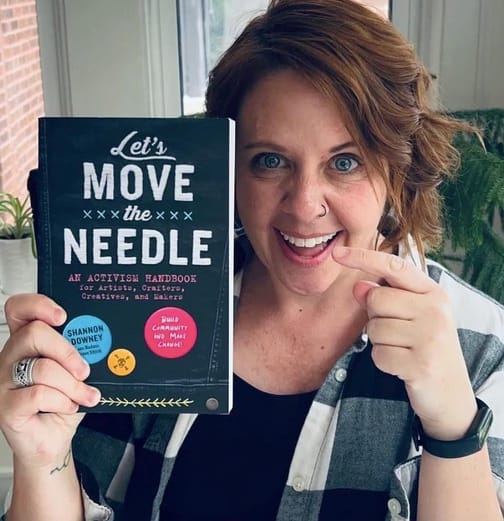

Mies Boissevain-van Lennep's project, and her emphasis on women's solidarity and "right to play a part in forging [their country's] future" feels like a strong thread of connection to our next writer's focus on "craftivism." Shannon Downey is a lifelong activist who also understands how powerful sewing can be. Her book, Let's Move the Needle: An Activism Handbook for Artists, Crafters, Creatives, and Makers centers the action element.

It isn't a pattern book, but it does provide a larger pattern. Downey gives us her step-by-step guide to the process of coming into community with others, to work on social issues through the vehicle of craft. It's a spirited, informative manual, full of helpful examples, guiding questions, and organizational tips.

Downey clarifies her concept of craftivism: "Craft is wildly valuable, but not all craft is craftivisim. It is a big deal to call yourself an activist or a craftivist, because it does, in fact, demand that you take action on behalf of the issues that matter to you. Craftivism is not performance art" (60).

If you are new to or hesitant about becoming active about issues, this book is a great place to start. It is extremely practical. Downey helps you sound out your views, get out of your comfort zone, learn more about yourself and the issues, and chart out an action. She just happens to do it through the medium of needlework. As she says, "Craft has been the hook, but activism has always been the goal." Craft engages people physically and mentally, it promotes focus that still allows for conversation, and can be done easily in groups.

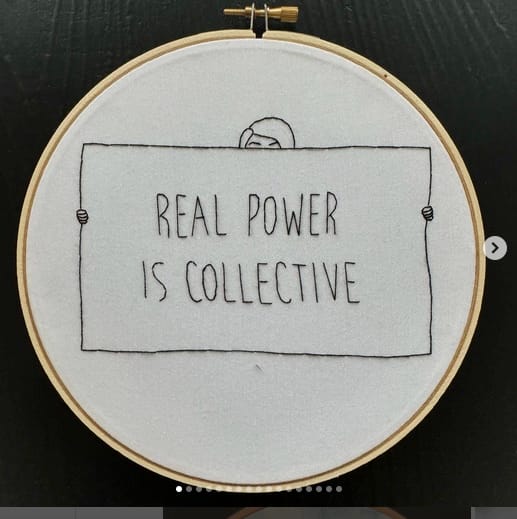

"Craft can be a profound vehicle for so many tactics."

Downey has a great track record of using craft to open conversations on tough subjects, and then helping people find pathways for group action: "I've used it to gather diverse groups of thinkers to problem-solve and strategize domestic violence initiatives in their community and to formulate and uplift counternarratives around queer and feminist issues. I've used it to educate folks about issues and the different ways of taking action in service of those issues. Most important in all of these situations, craft has been a mechanism for bringing people together" (62). And as a seasoned organizer, she doesn't sugar coat anything. She's clear-eyed about both the possible ecstasies and agonies of bringing people together.

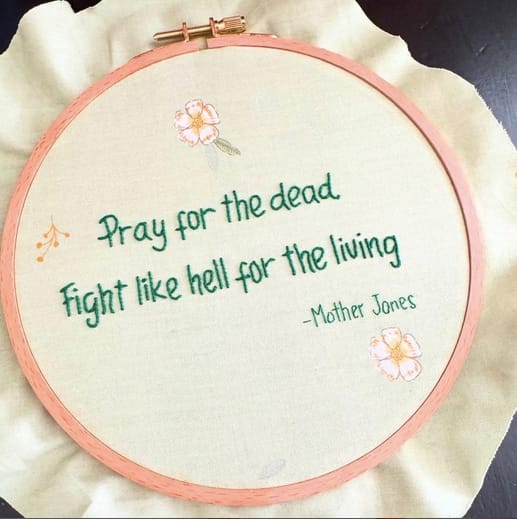

Even with all her emphasis on practicalities, I especially love how Downey makes space for wonder:

Wondering is time spent just thinking, letting your mind go where it wants. There is great overlap between being an activist and being an artist, and it lies in this experience of wonder, curiosity, contemplation, and thinking. It is the experience of developing a creative process. Wonder is key to identifying patterns. It cracks open the potential for reimagining what could be. We need creative minds to see through the fog and envision our communities, societies, and world as they could be" (101).

You can find more examples like these of her work at her Instagram account, @badasscrossstitch, and she does have patterns available (some free!) at her site: linktr.ee/BadassCrossStitch

If you are time- and focus-stressed, but would like a boost from Downey's energy, sense of humor and verve, check out this podcast interview with singer-songwriter Jess Klein. Downey shares her own backstory and an outline of the book, along with lots of emotions and laughter.