Post #5: Excavating History, Fathoming the Present, and Envisioning the Future

"Capitalism requires an ever-broadening disposable class of people in order to maintain itself, which in turn requires us to believe that there are people whose fates are not linked to our own: people who must be abandoned or eliminated" (32). Kelly Hayes & Mariame Kaba, Let This Radicalize You

This week we continue to witness the machinations of a regime which is actively and illegally disposing of immigrants in an El Salvador prison camp known for its torturous conditions. These individuals have been deprived of due process and labeled terrorist without evidence. We've also heard an expressed desire to build more camps for U.S. "homegrowns" and "unproductives." Do you hear the echoes? While less overt in the first presidential term, these attitudes were clearly present, which is why there is so much Nazi-related material front-loaded on our Learn, Imagine, Act resource list. (Find the list here: https://finding-throughlines.ghost.io/how-did-we-get-here-and-where-might-we-go-next/ )

I did not receive a strong education in the history of Nazism. Furthermore, I learned about it long ago, at an age where I had almost no lived experience to help me assimilate it as knowledge. And, full disclosure: I've realized by now that even when I think I have a general knowledge of something, close investigation of the specifics often leaves me shocked at how ignorant I've actually been. I can't be the only one like this? Maybe what I share here will be of use to others.

I've been reading Nazi Billionaires: The Dark History of Germany's Wealthiest Dynasties. This is David De Jong's painstaking documentation of the ways Nazi industrialists amalgamated wealth and power, supporting Hitler and furthering their gains through the Aryanization process. Gains their descendants still enjoy. I'm finding it a hard slog, following the actions of such heartless, insatiable men. For this reason, its worth adding Éric Vuillard's short, sharp, and poetic book, The Order of the Day, to our list. He introduces us to many of De Jong's cast of characters, but through brief, penetrating vignettes. I'll be sharing several of Vuillard's observations here in the context of current events.

I'm also bringing in ideas from Hayes and Kaba's book, Let This Radicalize You: Organizing and the Revolution of Reciprocal Care. I find their counsel useful, as we consider what we do with the Nazi material and it's modern parallels. And their concept of reciprocal care is one we very much need to cultivate. Seasoned activists and organizers, they have worked in resistance movements for transformative justice, particularly around incarceration.

Early in their book, they raise a key question:

"When we try to change the world, when we create containers for work, initiate relationships, or chart strategic paths forward, we are always battling assumptions. What myths underlie those assumptions? How can those myths be ripped out from under the lies they prop up? How can inevitability—a construct of the wicked—be ripped apart?" (5)

In this moment, families, caring institutions, and social structures are being ripped apart by a regime hostile to reciprocal care. So it is of the utmost importance that we expose myths and lies, and overturn what the wicked want us to believe is inevitable.

This is a tall order, when, every day, concerned citizens declare how challenging it is to simply fathom what is happening. The rule of law is being bulldozed at breakneck speed. And, added to our sense of facing an unstoppable juggernaut is the specter of consent to it. The majority party in congress—as well as many law firms, media conglomerates, universities, businesses, and a portion of everyday people—appear to be accepting the coup.

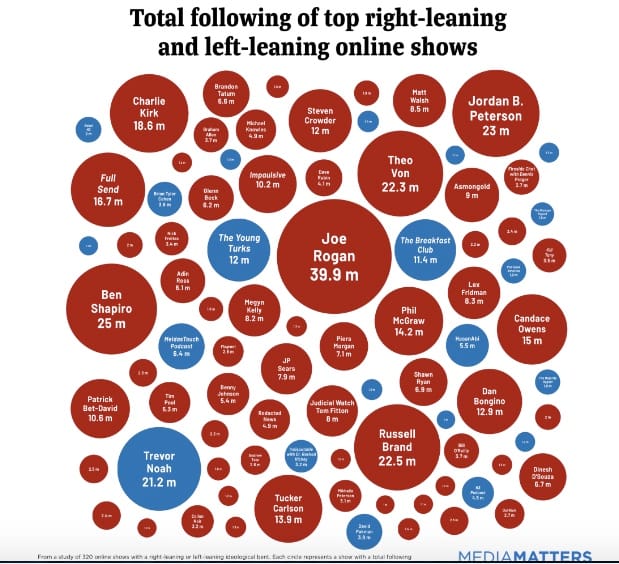

I find it helpful, however, to consider Hayes and Kaba's assertion that "most people are merely cooperating with the world as they understand it, either under the threat of violence or because they are navigating the illusions that were constructed around them" (45). I would add that these illusions have had some time to harden into a distinct ideological environment. Consider the right-leaning dominance of the airwaves in this example: https://www.mediamatters.org/google/right-dominates-online-media-ecosystem-seeping-sports-comedy-and-other-supposedly.

None of this is an "excuse" for cooperating with brutal power structures, but rather an attempt to identify different facets of our situation. How does it feel to apply Hayes and Kaba's description to some of the people you may disagree with? Or to yourself?

Hayes and Kaba argue that unlike the majority who are experiencing the conditions, the "people driving those conditions are a relative minority whose greed and violence does not define all of humanity, no matter how much they would like us to suppose it does" (45).

This is well worth pondering. If the authors are wrong, the inevitable will proceed on schedule. If they are right, and we nevertheless acquiesce to the idea that greed and violence is endemic to our population, we may seal our own fate. If we don't acquiesce, we at least have a chance for change.

When we look at the greedy minority that has now assembled around and even infiltrated the government, some throughlines and parallels emerge with the men profiled by De Jong and Vuillard. Of the Nazi billionaires, Vuillard warns us: "Don't believe for a minute that this all belongs to some distant past. These are not antediluvian monsters, creatures who pitifully faded away in the 1950s . . . . These names still exist. Their fortunes are enormous" (129).

He writes of how these "clergy of major industry" were called together by Reichstag president, Hermann Goering in 1933, to raise funds for Hitler: "there they stand, affectless, like twenty-four calculating machines at the gates of Hell" (17). He forces us to face the reality: "these twenty-four men are not called Schnitzler, or Witzleben, or Schmitt, or Finck, or Rosterg, or Heubel, as their identity papers would have us believe. They are called BASF, Bayer, Agfa, Opel, IG Farben, Siemens, Allianz, Telefunken. By these names we shall know them"(16).

And the outcome he describes was not inevitable, but it is nonetheless true:

"In fact, we know them very well. They are here beside us, among us. They are our cars, our washing machines, our household appliances, our clock radios, our homeowners insurance, our watch batteries."

In addition to those named above, Daimler, BMW, and Shell also profited from forced labor by prisoners taken from a long list of camps. IG Farben even "operated a large factory inside the camp at Auschwitz" (127).

Vuillard offers more telling details about Gustav Krupp: "For years, he had borrowed deportees from Buchenwald, Flossenbürg, Ravensbrück, Sachsenhausen, Auschwitz, and many other camps besides. Their life expectancy was a few months. The prisoners who managed to avoid infectious diseases literally died of starvation" (127). These "borrowed deportees" are the logical extreme of capitalism's appetite for the "disposable class of people." Nazi ideology was the mythology paving the way for these practices.

And what are such practices—the consuming of human lives for the accumulation of wealth—if not a form of cannibalism?

It took time for the full horror of this to unfold in the 20th century. But the fundraising event that kicked things off would lead to these kinds of statistics 10 years later: "Of the six hundred deportees who arrived at the Krupp factories in 1943," Vuillard tells us, "only twenty remained a year later."

In a final ghoulish gesture before transferring control to his son, Gustav Krupp established "Berthawerk, a forced-labor factory named after his wife, which he probably meant as some kind of tribute. The workers there were black with filth, infested with lice . . . . They were rousted awake at four-thirty, flanked by SS guards and trained dogs; they were beaten and tortured" (128).

From Vuillard's perspective, the 1933 meeting between Goering and the industrialists was not "a unique moment in corporate history," but rather "a perfectly ordinary business transaction" (15). "Corruption," he argues, "is an irreducible line item in the budget of large companies, and it goes by several names: lobbying fees, gifts, political contributions" (14). Furthermore, of these operatives, "all would survive the regime and go on to finance many other parties" (15).

It is not a stretch to imagine how violent the greedy could become, given the extreme wealth, power, and influence of our billionaire class, combined with the erosion of the Supreme Court, the goals of Project 2025, and the behavior of our head of state. And this is where it is helpful and hopeful to return to Let This Radicalize You, so that we don't despair.

In a chapter entitled "Care is Fundamental," Hayes and Kaba consider a 2021 National Intelligence Council report, which issued various projected scenarios regarded as possible by the year 2040. Of the five scenarios, one imagines the possibility that:

"Across the world, younger generations, shaped by the COVID-19 pandemic and traumatized by the threat of running out of food, joined together across borders to overcome resistance to reform, blaming older generations for destroying their planet. They threw their support behind NGOs and civil society organizations that were involved in relief efforts and developed a larger global following than those governments that were perceived to have failed their populations" (77).

I'd like to imagine that older generations might also lend a hand in helping create such an eventuality.

Hayes and Kaba respond that "if the death-makers who manufacture our oppression can imagine us remaking the world, surely our own visions of change can far exceed what is written in such reports—and can ultimately be realized" (78). But the only chance of this coming to pass is if we act now on our visions and our moral convictions, raising our voices, supporting those civil society organizations, and demanding caring and accountable government.

Our fates are linked. We must refuse to abandon each other, and we must make every effort to rip apart the construct of inevitability being imposed on us by rapacious billionaires and power hungry grifters.