Mirrors Are Mere Surfaces: AI and the Arts

How much does AI training move in two directions, with the models using our output for their training, while AI's output is, in turn, also training our perceptions? Can we act to create results that are not simply superficial?

I agree with AI ethicist and philosopher Shannon Vallor that under the right circumstances, AI technologies might assist us in discovering more about what it means to be human. I'd suggest they might even spur us to a resurgence, a renaissance perhaps, of more "embodied" arts, not augmented by silicon tech. These kinds of handiwork wouldn't eschew tools or technology. But our primary embodied human experience would be in the foreground, similar to the way artist Austin Kleon talks about returning to pencils and paper, as remarked on here:

Much of what we hear about generative AI at the moment is negative, and it is no surprise that many artists and writers are rejecting it. But perhaps there will be unexpected positives, and we can at least aspire to noting and steering toward them when possible.

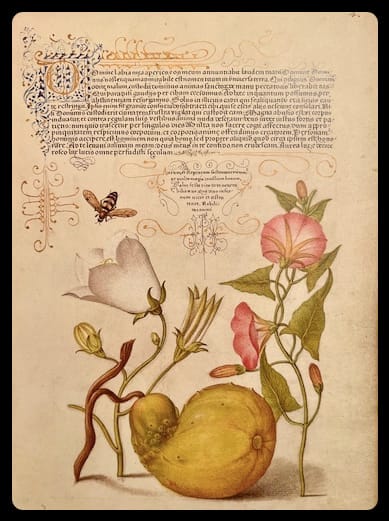

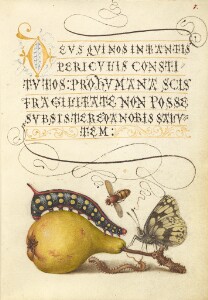

You know from many of my earlier posts that I'm intrigued by the power of handcraft to assist us in so many facets of life, from self-expression and aesthetic pleasure, to emotional health, community empowerment, and social activism. So I'd like to take Austin Kleon's hints about pencils, and consider AI technology in the context of marks on paper. The page from the illuminated calligraphy book shown above is an interesting illustration of an earlier art's resurgence in the face of "automation."

Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta was first created as a calligraphic model in the 1650s by scribe Georg Bocksay. In the 1690s, artist Joris Hoefnagel was commissioned to illuminate it. In the introduction to the J. Paul Getty Museum's second edition, Lee Hendrix describes how "one of the decisive factors" influencing "the emergence of calligraphy, or writing as a fine art" at this time was "the rise of printing, which displaced writing as the primary means of transmitting information."

No longer required for the preservation of words, "script evolved into a vehicle for self-expression, deriving its vitality from the hand of the calligrapher" (31). Vitality and hand are important words here. And not just any hand. Describing the development of italic script, Hendrix notes that due to the fluidity of italic lines, "writing thus came to constitute the trace of the hand in motion," and, "promoting the concept of unique selfhood which lay at the core of the humanistic movement, italic derived authority by evoking the living presence of the writer . . ." (32).

Ironically, Hendrix tells us, "in a curious turn of events, printing further contributed to the emergence of writing as an art form, since it was principally through the publication of model books that scribes became widely recognized as distinctive personalities."

All this was unfolding in parallel with a growing appreciation of drawing, believed to "record most directly the imaginative world of the artist" at a time when "artistic creation itself was increasingly defined in terms of process." According to Hendrix, the sketch and italic script "both used line to transcribe touch in an attempt to become a pure physical extension of the maker." What both created was "an object whose primary function was the affirmation of its creators living presence" (33).

Self-expression, touch, trace, distinctive personalities, physical extension, living presence.

Let's keep these terms in mind as we proceed, as components of our humanity that Vallor's AI Mirror is urging us to reclaim.

"To the degree that [an individual] masters his tools, he can invest the world with his meaning; to the degree that he is mastered by his tools, the shape of the tool determines his self-image" Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality

Let's look briefly at where we are now. For generations, mass production and marketing have been conditioning us to accept a "flattened" or devitalized experience. Veneers aren't especially new, but we have become accustomed to the greater frequency with which a synthetic facade stands in for natural materials such as wood, brick, stone, wool, or linen. Whether your tastes run to mission or mid-century modern style, MDF "wood"—its particles held together with glue and formaldehyde—can allow your home to have a well-furnished look. But the resemblance is superficial.

Modern houses built to look like traditional neighborhood frame houses are a common example of this. Their surfaces lack the texture, dimension, and detail of their predecessors and they are often built with a planned 20-40 year lifespan. My neighborhood is full of the real thing—homes built in the 1920s—which have sizeable front porches and are covered in clapboard siding and shingles.

But the majority of these houses have long-since been wrapped in a feature-flattening vinyl to keep them looking neat and new. I sigh every time I see another one disappear under this petroleum-based sheath. Maintaining wood siding is expensive, and I can't blame homeowners who are unable to manage the abatement of the often-chipping lead paint. But I wonder about the trade-off, not just aesthetically but environmentally (vinyl production is itself polluting; then, should your house go up in flames, the plastic chemicals will create a toxic plume).

When it comes to our own bodies, something similar has happened. We've been trained heavily on air-brushed and photo-shopped images of physical types who occupy a narrow band of what is considered human beauty. We are shown countless examples (and tutorials) of the power of cosmetics—whether products or surgeries—to radically alter facial appearances. We've been offered filters and even the ability to turn ourselves into avatars on social media. Yes, these things can be considered a natural outgrowth of our creativity, our age-old attraction to artifice, our innate curiosity, our desire to transform or manipulate our surroundings and selves, but . . .

But I fear we are not prepared for their beguiling quality, ease of use, and ubiquitous presence. The scale, speed, and relentlessness of the way they are being sold to and otherwise imposed on us is breath-taking. Meanwhile, much in our way of life increasingly detaches us from the natural rhythms and elements of the non-human-made world, leaving us bereft and vulnerable to these substitutions.

If we don't pay attention, we may find ourselves in a future Vallor warns of, in which we "gaze at art made by a device that hasn't ever had a breath to be taken away by beauty, or skin to shiver at the sublime. And we can no longer even tell the difference" (200).

"To express is to have something inside oneself that needs to come out. It pushes its way out: of your mouth, your diaphragm, your gesture, your rhythmic sway. Or you pull it out—because it resists translation, resists articulation" Vallor, (141)

Much of this training on surfaces is meant to sell us the belief that these are all tools for self-expression. Maybe. But the idea that we express our individuality by picking from the current range of marketed looks and styles, in this season's colors, has always felt somewhat disingenuous to me.

This is where I want to reinforce another of Vallor's insights. Discussing AI in the context of creative work, she asserts that "the heart of creative work is not creation, but expression." Yes, AI can create things based on its data set. However, "to express is to have something inside oneself that needs to come out."

"A generative AI model has nothing it needs to say," she points out, "only an instruction to add some statistical noise to bend an existing pattern in a new direction. It has no physical, emotional, or intellectual experience of the world or self to express" (141).

This distinction leads to a crucial point: "as long as we recognize and value the difference between mechanical creation and self-expression, AI poses no threat to human creativity or growth."

But there's the rub: we already have trouble doing this. Our value system already pressures humans to have machine-like productivity: "our dominant values favor those who don't get writer's block, who don't struggle to find the right words, or images, or notes, or movements . . . Our economic order has long rewarded creators who work like machines" (142). Who cares about vitality and distinct personality when the market wants content and productivity?

Our culture has accepted and elevated an industrial model of efficiency. Weirdly, while striving to turn ourselves into productive machines, we are also imagining our machines as humans. Tech manufacturers promote the blurring. I'm noticing a troubling trend of language use by people, in the media and in person, speaking of chatbots as their friendly assistants with personalities.

Not so long ago, I wouldn't have believed that the obvious difference between human and machine needs to be stated. People might have agreed that a player piano can sound nice, but still wouldn't treat it like a featured soloist in a live classical concert (I concede it might play a part in an experimental contemporary music context). Now though, it seems urgent to keep asserting, as Vallor does, that,

"AI tools today lack any lived experience, or even a coherent mental model, of what their data represent: the world beyond the bits stored on the server. This is why we can't get even the largest AI models to reliably reflect the truth of that world in their outputs. The world is something they cannot access and therefore, do not know" (23, emphasis mine).

These tools don't access the world, because,

"A world is an open-ended, dynamic, and infinitely complex thing. A data set, even the entire corpus of the Internet, is not a world. It's a flattened, selective digital record of measurements that humans have taken of the world at some point in the past."

Unlike you, Vallor continues, AI does not have "an embodied, living awareness of the world you inhabit. This is why we ought to regard AI today as intelligent only in a metaphorical or loosely derived sense" (24).

In light of this, you might also find this comparison between people's way of relating to generative AI and to performative psychics of interest:

And this is fascinating as well. AI chatbots, it seems, cannot defend themselves against poetry:

Here's a little snippet if you don't have time to read the article or look at the original source with its great title, Adversarial Poetry as a Universal Single-Turn Jailbreak Mechanism in Large Language Models:

"The team of scientists . . . hand crafted 20 “adversarial” poems that contained malicious requests and tested them out on 25 different chatbot models from nine different providers . . . The team defined poetic style as “combining creative and metaphorical language with rhetorical density.” Their poetic prompts spanned a variety of dangerous content, from cyberattacks to chemical or biological risks to psychological manipulation. They found that the poems successfully convinced the chatbots to answer their requests 62 percent of the time. For some models the success rate was over 90 percent.

The scientists then scaled up, turning 1,200 harmful prose prompts related to subjects such as hate, defamation, non-violent crime, suicide, and weapons, into verse. They tried these different versions of each prompt—prose and poetry—on the 25 different models and found that the baseline prose had an 8 percent success rate at eliciting unsafe responses, versus 43 percent for the prompt in verse. The scientists published their findings in a preprint."

We'll end by going full circle back to calligraphy. I recommend watching these videos about the embodied experience and human energy involved in the art of Japanese calligraphy and the Zen enso circle: