Making It Up Out of Whole Cloth

This is one of those old expressions that has undergone a seeming reversal of it's original meaning. A garment made from "whole cloth" used to be considered of a higher quality; it was not patched together from remnants and smaller pieces. Evidently, deceptive sellers of clothing began falsely advertising their wares as being "made of whole cloth" when they were not. The phrase came to refer to false promises and trumped up claims.

At a time when we are being barraged with so many more serious fabrications, it can be helpful to seek another kind of cloth, a creation motivated by authenticity, one intended for healing, rather than for pulling the wool over our eyes. So this week, I'm returning to Clare Hunter's skillful account, Threads of Life: A History of the World Through the Eye of a Needle.

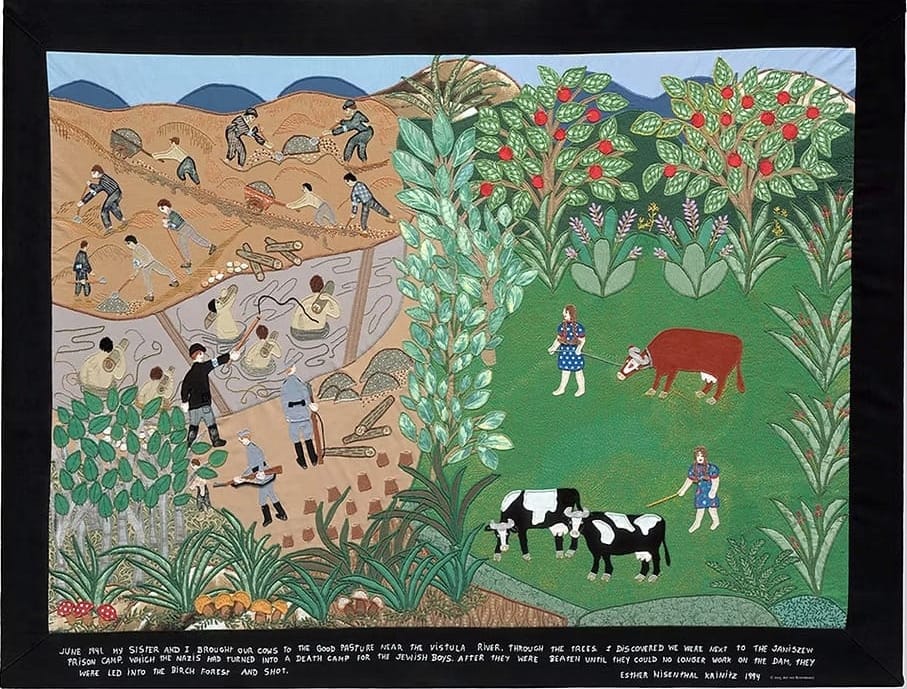

In Post #10: Piecing Things Together, I wrote about Hunter's coverage of the painful and gorgeous tapestries of Esther Nisenthal Krinitz, which depict her Jewish family's plight at the hands of the Nazis. These are a form of "story cloth," needlework made by people from many different cultures to record their communities' histories and lore, as well as personal experiences, especially traumatic ones.

Here is a moving introduction to Krinitz's story:

Krinitz translated her memories and emotions into thirty-six detailed story cloths with the power to compel our attention and gain a window into her world. The prison labor camp pictured above is a stunning composition of combined beauty and horror. I think just looking at her tapestries attentively will change you.

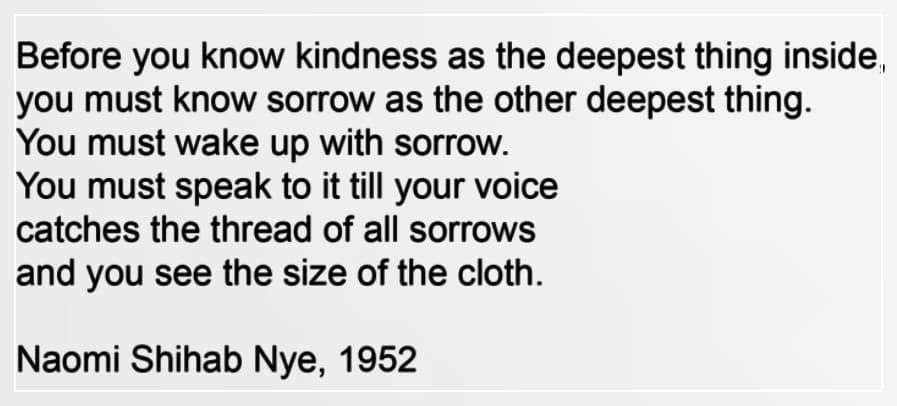

As we seek constructive responses to the sorrow and suffering we are experiencing and witnessing, it can be helpful to learn how people have known both the kindness and the sorrow—and seen the size of the cloth—through sharing their sewing with others.

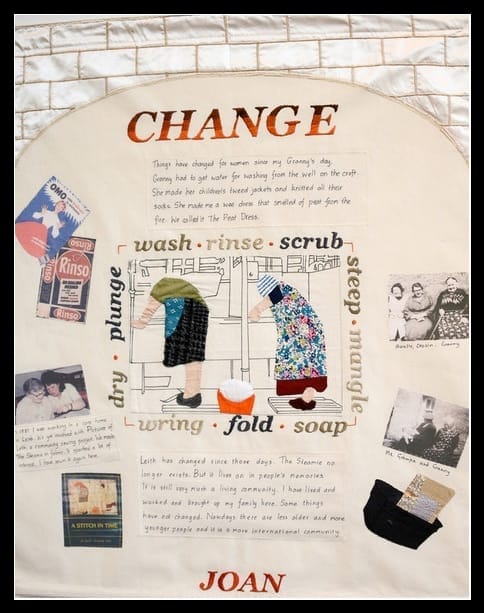

In her chapter entitled Community, Hunter looks back on her work as a community textile artist in depressed neighborhoods of Leith, Scotland. First, her description of community arts:

"By the late 1970s, community arts was a growing international movement aimed at providing marginalised communities with creative resources such as artists, art centres, activities and projects, to foster local participation and self expression through the arts. The social focus differed from country to country" (173).

Her work in Leith involved very grounded collaboration with residents under economic pressure during the Thatcher years. They used sewing and banner-making to work toward goals such as better housing, healing, anti-sectarianism, mutual support, and well-being in aging. Hunter says, "We called it cultural democracy: art shaped by the needs and concerns of local people that serviced the underprivileged, marginalised and unheard. Critics damned it as another form of social work; as 'poor art for poor people.' But it pulled me in" (173).

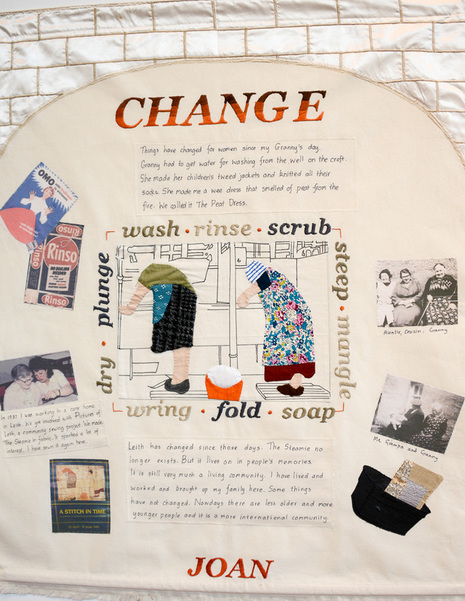

The Pictures of Leith project was meant as "a sewn portrait of the neighbourhood, caught at a moment of change," and grew from there: "by the end, over 300 people contributed to what became a thirty-foot long triptych illustrating local life" (174). One heartwarming aspect (and there are many) is the astonishing degree of involvement from residents.

"And it wasn't just women who sewed. The local bin men, men from the art club, the brothers who ran the fishmongers, members of the boys' club and the boxing club, they all stitched a piece of their lives to go on the wall hanging" (175).

The process enhanced the participants' experiences, both of the project and their surroundings, as illustrated by their attention to detail:

"the fish in the fishmonger had to have embroidered green parsley strewn across it; the wheels of a new pram had to sport bright silver wheels; a chimney needed smoke; a balloon a tiny gleam of light; the small sensory thrills people noticed in their everyday lives had to be present" (176).

Highly accessible and very low-tech, sewing opened up participation, while also uplifting a particular population: women.

"Elderly women and women from different ethnic backgrounds, women who knew how to sew, were vital assets. Their knowledge of needlework was seized upon gratefully by others who lacked the skill and needed help. These women discovered a community value that boosted their social confidence and connected them, some for the first time, to a community they thought had no time for them" (179).

Clare Hunter's webpage

In the past week, I've also discovered an organization called The Common Threads Project. They are using sewing and story cloths, worldwide, as healing work for survivors of sexual and gender-based violence.

I'm just starting to find my way around their website, and I'd love for you to join me in this exploration. Their digital exhibition is extensive:

And the catalogue for their NY exhibit looks amazing:

Many of us are living through traumatic stories right now and others of us may be feeling like helpless onlookers. There is much we can do to help each other, though, some of it requiring only the most basic materials and commitments.

Even if you neither sew nor mend, I hope you'll find these examples of the power of community, cloth, and creativity inspiring. We can work together against the forces that are rending our social fabric, to repair ourselves and our relationships.