Hans Asperger and Nazi Psychiatry: Diagnosing History

The aim of this history is not to indict any particular figure, nor is it to undermine the positive discussion of neurodiversity that Asperger's work has inspired. Rather, it is cautionary tale in service of neurodiversity—revealing the extent to which diagnoses can be shaped by social and political forces, how difficult those may be to perceive, and how hard they may be to combat. (16)

Soon after RFK Jr. announced his plans for an autism registry/database, Timothy Snyder posted on social media that this would be a good time to (re)read Asperger's Children. I promptly added it to the Learn, Imagine, Act list.

Snyder's was the first blurb on historian Edith Sheffer's book when it came out in 2018. He notes that while the world of the 1930s and 40s Austria "is not our world," he asserts that "the connections, the habits of mind, speech, diagnosis, are more powerful than we think." On a cautionary note, Snyder continues: "Sheffer helps us to understand why we classify our children the way we do, and helps us to ask, as we must, just what kind of world we are making for them." After reading the book, I concur. I also wonder whether Asperger's case suggests we've been too eager to find heroic figures—he was not Schindler in a pediatric unit, after all.

Diagnosis is the key word here. As Sheffer tells us in the introduction, "this book suggests a new lens on the Third Reich—as a diagnosis regime." How the Nazi eugenics system classified humans on a scale of political and social "value" was a somewhat fluid and evolving process. The stakes for those categorized were extremely high, as neuropsychiatrists "played the largest role of any professional group in the medical cleansing of society, in the development of forced sterilization, human experiments, and the killing of those perceived to be disabled" (18). The following paragraph encapsulates what Sheffer's analysis will proceed to illuminate in striking, often horrifying, detail:

What, exactly, was being diagnosed? In Asperger's circles, proper race and physiology were necessary for joining the national community, or Volksgemeinschaft. But community spirit was also required. One had to believe and behave in unison with the group. The vitality of the German Volk, or German people, depended upon the ability of individuals to feel it. The fascination with social cohesion spotlights the importance of fascism at the heart of Nazism. (19)

Related to this is the concept of Gemüt. The focus of in-depth discussion later in the book, this multi-faceted term "came to signify the metaphysical capacity for social bonds." Psychiatric use of such a quasi-religious term as part of an "objective" assessment process should cast doubt on the findings that arose from Asperger's work with children. But there's so much more to doubt. Sheffer's evidence requires we question even the seemingly positive selections from Asperger's thesis, popularized by British psychiatrist Lorna Wing in 1981. Here, Sheffer summarizes what the rest of the chapters carefully unpack:

Files reveal that Asperger participated in Vienna's child killing system on multiple levels. He was close colleagues with leaders in Vienna's child euthanasia system and, through his numerous positions in the Nazi state, sent dozens of children to Spiegelgrund children's institution, where children in Vienna were killed. (16)

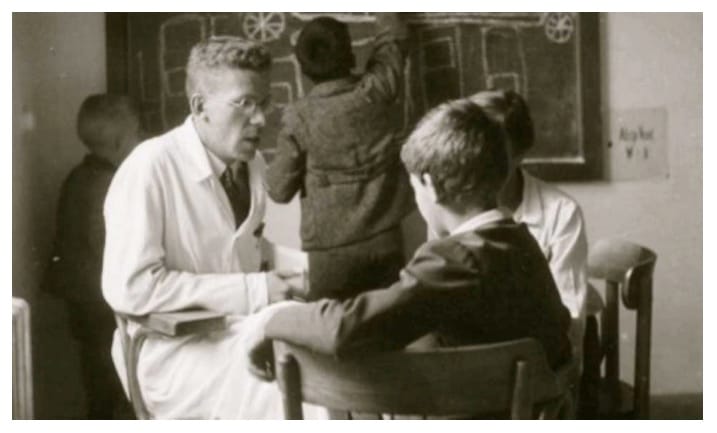

The book traces the drastic movement away from the progressive origins of both the Curative Education Clinic at the University of Vienna's Children's Hospital where Asperger was being mentored, and the Steinhof Psychiatric Institute where Spiegelgrund was located, after the annexation of Austria in 1938. Sheffer describes how "child psychiatry had an important place in the Reich's ambition for a unified, homogenous national community," (67) and changes in staffing and administrators reflected those goals. Given our current situation, it is a frightening study in the ideological overhaul of institutions.

After the Anschluss, medical faculty at the University of Vienna were required to "swear a loyalty oath to Adolf Hitler and register their bloodline with the administration." The results were devastating, as the "medical school removed 78 percent of its faculty, predominantly Jews, including three Nobel Prize winners. Out of 197 physicians, only 44 faculty remained," while "two-thirds of all Vienna's 4,900 doctors and 70 percent of its 110 pediatricians lost their positions." (79).

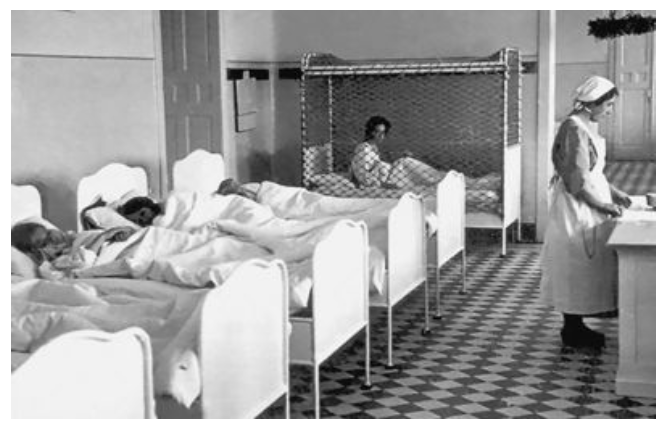

Steinhof Psychiatric Institute, once a "modern, progressive asylum" became, under the Nazis, "responsible for more than 7,500 deaths between 1940 and 1945—through starvation, deliberate neglect, or mass transfers of patients to the gas chambers." When the deportation of 3,200 to be gassed "emptied enough room to house hundreds of children," the tragedy of Spiegelgrund, with its "death pavilions" for at least 789 children, began.

The Third Reich harnessed a curious juxtaposition of efforts, of total war versus erudite debates, of genocide versus journal articles. But the task to mold the mind mattered, as psychiatrists discussed the finer points of Nazi philosophy while carnage raged around them. (211)

Asperger was a professed Catholic and, even while functioning in key positions within the Reich's medical establishment, never joined the Nazi party. Many of his associates were directly involved with the most monstrous policies and themselves directed experiments or carried out the killings of children. This was not euthanasia in the sense of being used only for the terminally ill. He could not have been ignorant of this.

To better understand how Asperger navigated this political and professional terrain, Sheffer examines notes and proceedings from professional conferences and organizations (one of which Asperger co-founded); his writings about his work and that of his mentors and colleagues; patient and other medical files; and other records. She identifies changes in Asperger's language, attitude, and diagnoses between 1937 and 1944 that correspond with Nazi party influences.

The Reich's systems of extermination depended upon people like Asperger, who maneuvered themselves, perhaps uncritically, within their positions. Individuals such as Asperger were neither committed killers nor even directly involved in the moment of death. Yet, in the absence of murderous convictions, they made the Reich's killing systems possible. (237)

Asperger continued his children's practice and was active into the 1970s, having been "cleared of wrongdoing after the war." Sheffer is unequivocal: "while Asperger may well have endeavored to protect some children who could face death, it is nevertheless documented that he recommended the transfer of others to Spiegelgrund, dozens of whom were killed . . . he had numerous, volitional ties to the euthanasia program and it pervaded his professional world" (230).

He wasn't the only one who survived with his reputation and career intact. As Sheffer points out, "many other perpetrators emerged virtually unscathed. Even top Reich-level euthanasia figures, Hans Heinze and Werner Villinger, had flourishing postwar careers as Germany's leading psychiatrists" (226).

It's a gruesome legacy: "body parts of children killed at Spiegelgrund continued to circulate among Vienna's research laboratories, the basis of its physicians' publications for decades." Awarded an Honorary Cross for Science and Art in 1975, "Speigelgrund doctor Heinrich Gross published thirty-eight articles over twenty-five years—several based on the preserved brains of over four hundred children that he had harvested at Spiegelgrund"(227). Those remains were finally buried in 2002.

This is a difficult book to read, and must have been even harder to research and write. The cruelty of the "treatments," the photos of murdered children, and the stories of survivors are haunting. The parent of a son with an autism diagnosis, Sheffer has done tremendous service on behalf of all those who suffered—and for all of us now—in bringing this information to light.

This short article provides a more concise list of examples and evidence of Asperger's complicity with Nazi eugenics, as well as specific examples of his anti-semitism that have not been as fully described elsewhere. It also has links to additional references and resources:

This compelling New Yorker article from 2023 tells a related story, with some overlapping characters. While the title makes it sound set in Nazi Germany, the perpetrator carried out her methods in an Austrian children's facility for decades after the war, and remained active in scholarly circles up until 1980. It shows the lasting reverberations—traced like radioactive fallout in individual lives—of the postwar continuation of Nazi psychiatry:

We are now in a time of massive firing, defunding, hunting, sorting, and deporting. Detention centers with deplorable conditions in the U.S. are growing rapidly, and in addition to seeking to outsource prisons, this regime has signaled interest in establishing "health camps" and medical surveillance. With all this in mind, I'd like to end with some additional statistics from Sheffer, numbers that should make us ask what kind of world we want to make for everyone: