Fever Pitch: Dethroning the Klan's Consummate Grifter

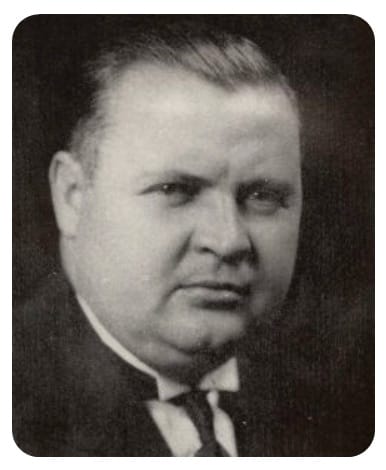

D.C. Stephenson, Grand Dragon of the KKK in Indiana (aka Steve and The Old Man), was serving his twenty-year prison sentence when the lawyer who convicted him "asked him if he'd been serious about running for the White House. Steve said the plan was real. 'You wouldn't have called it President,' he said. 'The form of government might have changed. You might have had a dictator.'" (Egan, 350)

Timothy Egan charts the rapid rise and spectacular fall of Stephenson (1891-1966) in this fascinating look at a) the power of a charismatic conman to exploit the existing fears, bigotries, and proclivities of a large following, and b) the dramatic criminal case and deathbed testimony that altered what had been the burgeoning course of the Klan in the early to mid-1920s.

"I did not sell the Klan in Indiana on hatreds," Stephenson said. "I sold it on Americanism." (xvi)

Egan describes this central figure who rebuilt and rebranded the Klan in the Midwest:

"he had magnetism, unbridled energy, and a talent for bundling a set of grievances against immigrants, Jews, Roman Catholics, and Blacks into a simple unified pitch that made sense of a fast-changing America still dazed by the Great War" (15).

In just a few years Stephenson had charmed, bribed, bullied, and blackmailed his way into tremendous wealth and influence. Influence over businessmen, religious leaders, law enforcement officers, judges and politicians. By 1925 he was able to boast, with some truth, "I am the law in Indiana." And he had set his sights far beyond that state.

Stephenson was also a voracious and violent drunk, a rapist who assaulted numerous women—everyone from his wives to party guests, hotel staff, and his own stenographers—often drawing blood by brutally scratching and biting them. Egan's documentation of Stephenson's depravity is thorough, and at times made me feel almost nauseated.

This man created an enormous movement in "the Heartland," not far from where I grew up. In fact, Stephenson was still alive and still a danger to teenage girls when I was a kid.

Yet I had never heard of him, never learned how this second iteration of the Klan in Indiana,

"bombed homes and set fires. They didn't hide by day and only come out at night. They were people who held their communities together, bankers and merchants, lawyers and doctors, coaches and teachers, servants of God and shapers of opinion. Their wives belonged to the Klan women's auxiliary, and their masked children marched in parades under the banner of the Ku Klux Kiddies." (xxi)

I grew up driving through Indiana on the way to visit family in Kentucky, believing that the Klan was mainly a Southern phenomenon. Before reading this book, I didn't know about its renewal in the 1920s, in active outposts such as Oregon, Colorado, and several midwestern states.

"Stephenson had succeeded with an unusual formula for a mass movement: men were the muscle, women spread the poison, and ministers sanctified it all."(66)

In spite of materials that have more recently come to light, I suspect we will never know precisely what portion of Klan members joined willingly and who joined due to peer pressure, intimidation, and outright coercion. The overall numbers were high and grew quickly; the majority seem to have been eager to join. It didn't hurt that Indiana was 97% white.

The Klan managed to appeal to anti-immigrant sentiment, the Prohibition movement, religious fervor, and even women's suffrage, especially after Stephenson joined forces with the charismatic preacher from a Quaker background, Daisy Barr. With Barr's help, the "women's Klan had gone from nothing to nearly 250,000 in less than a year's time" (66). By 1923, the "Klan claimed 200,000 members in Ohio, and nearly an equal amount in Michigan and Wisconsin" (89). The state of Kansas had 60,000 members by 1924. For what we tend to think of as small town America, their rallies were huge, sometimes drawing 10,000 people.

"Sometimes we'd leave a wild party, slip into the robes, and go into church to pray with a bunch of new Klansmen . . . Stephenson would kneel down and pray as convincingly as any minister." Court Asher, Stephenson's pilot (122)

Stephenson and other Klan leaders also knew how to capitalize on existing conventions of group membership. Fraternal Orders were in their "golden age" then, Egan explains: "the United states was full of secretive clubs: Masons, Woodmen, Red Men, Elks, and Odd Fellows, with nearly 40 percent of adult males belonging to a fraternal order" (25). Stephenson parlayed his white-robed secret club into a fortune, taking a cut of the high initiation fee, quarterly membership dues, and costs for the "uniform." "In a given week," Egan notes, "he was taking in five times more than most Americans made in a year" (36).

In other examples of exploiting existing conditions or beliefs, Stephenson turned community gossip, leftover 19th-century vigilante groups, and the eugenics movement to his advantage. With the help of Daisy Barr, he created "poison squads" to spread disinformation using "the best-known clucks and gossips in every community, so that false stories could plausibly be true" (63). The poison could be swift and potent even in those low-information technology times: "the Klan prided itself on how quickly it could spread a lie: from a kitchen table to the whole state in six hours or less" and could "intimidate and frighten certain businesses, as well as local politicians" (63).

Stephenson recognized an opportunity in Indiana's history of "horse thief detectives." These were vigilante groups deputized, starting in the 1860s, to go after horse thieves. He recruited thousands into the Klan, to form his own militia. He used this "rogue arm of law enforcement to harass offenders of virtue," and, frequently, to cover for him in his own offenses against virtue. Establishing new chapters at the very time horses were giving way to cars, the Horse Thief Detective Association grew "from 8,000 deputies to 14,000 in little more than a year" (34).

Indiana had already been at the forefront of the eugenics movement, since the 1907 passage of sterilization laws. By the time Stephenson took to the stage to preach racial purity, over 2,000 Indiana residents had been involuntarily sterilized. State fairs ran "better baby contests" and Iowa eugenicist Harry Laughlin was promoting sterilization laws to other states and congress. Notably, "about 70,000 people across the United States would be forcibly sterilized," and "a special category of 'degenerates' was added in many of these states in order to sterilize homosexuals"(106).

As part of his anti-immigration campaign for the Klan, Stephenson rallied a crowd in 1923, telling them,

"'In reference to feeblemindedness, insanity, crime, epilepsy, tuberculosis and deformity, the older immigrant stocks were vastly superior to the recent.' The new Americans were 'dregs from putrefied vomit," parasites, illiterate, dumb, lawless, with overactive sex drives" (104).

While this certainly sounds like "selling on hatreds," Stephenson assured his audience that preventing the immigration of "inferior races" was "a struggle to save America." Congress seems to have agreed; they passed the National Origins Act of 1924 with ease, a law Egan describes as "a Klan-blessed master design for the future of America." The act made drastic changes to immigration patterns by reducing quotas (171).

A Fever in the Heartland also highlights those who opposed and resisted the growth of the Klan, including the intrepid Notre Dame students who "routed" a Klan march in South Bend intended to intimidate the Catholic institution. As Egan notes,

A handful of Hoosiers were heroic—two rabbis, an African American publisher born enslaved, a fearless Catholic lawyer, a small-town editor repeatedly beaten and thrown in jail, a lone prosecutor. " (xxi)

One Hoosier, a most unwilling participant in her heroism, was twenty-eight year old Madge Overholtzer. Her desperate attempts to escape Stephenson's clutches after he kidnapped, raped, and mutilated her set the stage for his downfall. I will leave the coverage of this horrific incident, and the dramatic trial that ensues, to Egan's careful narration. His final discussion of the case provides much food for thought about a) what Stephenson's and the Klan's trajectory might have been had the court's conclusion differed, and b) how much the Klan could be said to have "succeeded" in much of its mission, regardless of its decline due to the trial's outcome. Egan is careful to point out that decades of bigotry, redlining, and lynching were still to ensue.

Timothy Egan has assembled the evidence and tells a riveting story of corruption, greed, and white supremacy. And with it, a sickeningly familiar picture of misogyny and sexual abuse emerges. For the reader, Egan's depictions of the vast, powerful network of Klan actors may induce despair about human frailty. However, the antidote is to be found in the Overholtzer family's courage, the prosecutor's moral commitment, and the jury's verdict. It is a difficult but important read.

photo from: https://hoosierhistorylive.org/mail/2024-06-29.html