Engaging with Other Minds: More on Art, Activism, AI

"I suppose, then, that these are the sorts of questions I have for us just now as we navigate the flood of machine-generated media: How will AI-generated images train our vision? What habit of attention does it encourage? What modes of engagement do they sustain?" L.M. Sacasas, "Lonely Surfaces"

Sacasas was writing thoughtfully about such questions back in December of 2022, when I was only just starting to notice an infiltration of AI-generated images in my social media feed. After my post last week concerning the ways we are being trained on surfaces, I was happy to discover this essay of his, delving into the different ways human-crafted images engage our attention as opposed to AI-generated. It is well-worth reading in its entirety, but this description of trying to look deeply at an AI "painting" stood out to me:

"But as I came back to the image and sat with it for a while, I found that my efforts to engage it at depth were thwarted. This happened when I began to inspect the image more closely. As I did so, my experience of the image began to devolve rather than deepen. When taken whole and at a glance, the image invited closer consideration, but it did not ultimately sustain or reward such attention."

Do the things we look at devolve or deepen our experiences of our world? And are we paying enough attention to notice which one is happening?

My personal experience with the painting at the top of this essay came to mind as I read Sacasas' observation:

"When I turn to Bruegel or Rembrandt, what I find, whether or not I am fully conscious of it, is not merely technical virtuosity, it is another mind. To encounter a painting or a piece of music or poem is to encounter another person, although it is sometimes easy to lose sight of this fact."

As I first stood in front of Anna Klumpke's painting of the washer women, it did indeed feel like an astonishing encounter. An encounter, moreover, with multiple layers of minds: the painter's, her subjects', and those of the painting's historical viewers.

For me, a strongly-communicated element of this experience is a sense of solidarity among women, and the elevation of devalued "women's work" to a subject of fine art. The women have individuality and presence. The scene is full of light and life, muscles and movement, skin and steam. Their task is not romanticized. They are set against cracked and besmirched walls, window panes covered in a patina of grime. Cobwebs hang above them. They are dressed in drab clothes and large, unshapely shoes, and their hair, that mark of Victorian femininity, is securely hidden under their plain headscarves. It's a large painting, like a window, and I stood there a long time, breathing it in.

Of course, if one glides past such an image in the act of scanning and scrolling, most of the experience of encounter will be lost. Time-strapped, over-stimulated, and constantly prodded toward the next new thing, we seem to have less and less access to deep engagement, even while our technology can potentially bring a world of such art out of galleries and into our homes for a closer look.

" . . . the skimming sort of reading that characterizes so much of our engagement with digital texts (and which often gets transferred to our engagement with analog texts) arises as a coping mechanism for the overwhelming volume of text we typically encounter on any given day," Sacasas, "Lonely Surfaces"

As an English professor, I've thought a lot about how this loss of encounter is true for writing and literary texts as well. It's why I was so intrigued years ago to read about an art professor's immersive assignment. To encourage students in her art history courses to "decelerate," she assigned them to spend 3 hours sitting alone in front of one painting in a gallery and record their observations.

Around the time Roberts wrote this, I had tried a similar, but pared down, activity as it applied to my students' experience of Wordsworth's poetry. Realizing that his work was intrinsically related to the rhythms and pace of walking—an activity that few of the students at my commuter-heavy campus ever engaged in—I asked them to take a 20 minute walk with their phone turned off, observing their surroundings and their felt experience. It turned out to be a difficult but revelatory 20 minutes, even if it did little to replicate Romanticism for my urban college students.

"The art historian David Joselit has described paintings," Roberts notes, "as deep reservoirs of temporal experience—'time batteries'—'exorbitant stockpiles' of experience and information."

What an evocative description and wildly meaningful way of orienting ourselves toward art! Unfortunately, I don't think there is much in our current educational experience that helps enough of us conceptualize this, and it's hard to imagine the rare assignment of these kinds being enough of an intervention to make a difference. We haven't learned how to appreciate the exorbitant stockpiles we humans have already created (and which AI-generated "art" basically plagiarizes from). It feels as though we are facing the AI onslaught unequipped to navigate it well.

This is where it helps to consider the advice of Elizabeth Sawin, author of MultiSolving: Creating Systems Change in a Fractured World. While acknowledging that when "dangers are so huge and existential, it can feel that our actions must rise to similar scales," Sawin argues that this isn't really true.

"Meet the emerging needs that you can," she urges us. "Tend and connect where you are able." For Sawin, this means that "in complex systems, even in tumultuous times—maybe especially in tumultuous times—you may have dozens of tiny opportunities every day to choose how to act, how to intervene, where to connect, and how to connect" (222).

As I have written about in earlier posts, craft as a form of activism can be a powerful avenue for tending, connecting, and intervening. I want to wrap up this first year of the Learn, Imagine, Act project with a celebration of this.

The arts and crafts offer (what can sometimes seem like tiny but) powerful opportunities, allowing us to share a visible, temporal experience of community and creativity. This comes through clearly in today's Guardian article, which describes knitters showing up to ply their needles together at protests, and provides links to other forms of craftivism that support marginalized groups and make political statements:

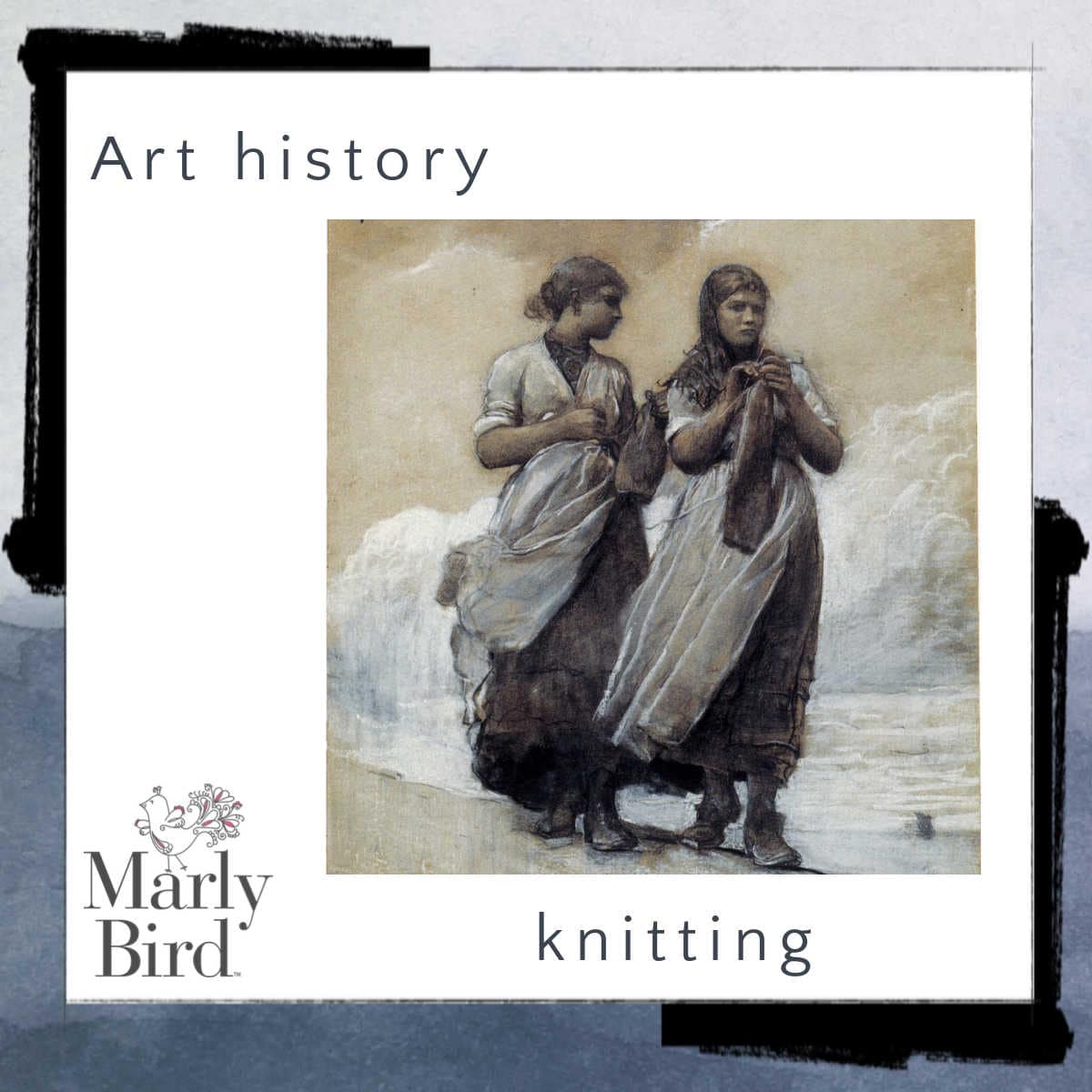

These modern fiber artists lead me back to Anna Klumpke. In another celebration of the work of women's hands, exhibited the same year as In the Wash House, Klumpke focuses on a lone knitter, Catinou. As stable and situated as the rocks and mountains nearby, she is a human force of nature. Catinou takes on an emblematic function: she represents all the unseen and unappreciated women who are, in effect, clothing the world.

Finally, for those of us experiencing stress, fatigue, and disillusionment as this year winds down, it can be a gift to refill our emotional reserves by spending a little time with paintings that are "deep reservoirs of temporal experience." Here's a link to a wonderful compilation of knitters in 19th-century art, full of examples like the one I'm closing this post with. May these "time batteries" recharge you!